Indigenous Activism on Environmental Issues on TikTok

Team Leads (FGV DAPP):

Danielle Sanches

Marcela Canavarro

Sabrina Almeida

Lucas Roberto

Team members and affiliations:

Juliana Valentim (University of Porto, Portugal)

Bia Carneiro (Centro de Estudos Sociais, Universidade de Coimbra, Portugal)

Mattia Mertens (Politecnico di Milano, Italy)

Harald Meier (Social Media Research Foundation)

Final presentation slides

Key Findings

Introduction

Research Questions

Query Design & Visual Protocol

Methodology

Findings

Discussion

References

Key Findings

- The platforms’ unique combinations of hashtags allow indigenous and indigenists profiles to drive affective content and engage in overlapping and interconnected conversations about advancing the environmental agenda.

- The study points to a trend towards increased protagonism of indigenous causes and a possible connection to environmental and social issues in the period studied.

- Findings suggest an ambiguity of indigenous issues’ messages and their connections with intertextual and cultural factors to make meaning. Future work can advance this exploratory study to analyse whether these become popular due to the seriousness of the issues or if they involve other conditions, such as fun or visibility.

The presence of indigenous voices on social media platforms has increased substantially in recent years in Brazil and has become relevant in the environmental-focused public debate, locally and globally. The micro video platform TikTok has emerged as a popular pivot for political messaging, self-expression, and digital activism, particularly for indigenous youth. In this sense, we present this exploratory digital research that aims to understand the information sharing behaviours of indigenous influencers on social media sites. For this, we deployed a network analysis of TikTok, Twitter and Instagram posts, selected through the query design of the hashtag #povosindigenas. We focused on the interconnected and overlapped topics that emerged when our sample’s profiles combined these with povos indigenas-hashtagged posts. Furthermore, we examined how indigenous profiles engage with the wider audience through political conversations and trends on these platforms.

Recent analysis indicates a growing interest in digital activism on TikTok, especially climate activism, with a greater focus on digital infrastructures and affordances. Research examines how TikTok’s features facilitate a unique kind of activism by helping non-expert users intervene in the public discussion, which can collectively abet, amplify, but also confuse discussions of global issues online (HAUTEA et al. 2021). However, the lack of research on digital activism led by indigenous peoples remains an understudied field.

During this study, we found the platforms’ unique combinations of hashtags allow indigenous and indigenists profiles to drive affective content and engage in overlapping and interconnected conversations about advancing the environmental agenda. Likewise, the study points to a trend towards increased protagonism of indigenous causes and a possible connection to environmental and social issues in the period studied. Moreover, findings suggest an ambiguity of indigenous issues’ messages and their connections with intertextual and cultural factors to make meaning.

Future work can advance this exploratory study through qualitative analyses of whether these become popular due to the seriousness of the issues or if they involve other conditions, such as fun or visibility. Researchers can also deploy semiotic analysis of clusters, seeking clues and short paths to comprehend such grouping in conjunction with the text analysis results.

We structured the report by first outlining the research questions that guide our analysis. Next, we explain the query design and the visual protocol used to extract data based on the #povosindigenas query. The methods and procedures used to collect the dataset are further detailed in the Methodology section. After evaluating the descriptive characteristics of the dataset, we outline the preliminary findings of this study, linking these to our research questions, examined in the Discussion section.

Overall, this project focused on the following main research question (MRQ):

MRQ: How do indigenous influencers engage with the audience on TikTok, Twitter, and Instagram?

We split the MRQ into two more research questions (RQ):

RQ1: What political and social uses emerge from these environments in this context?

RQ2: What are the trending thematics on each analysed platform?

By focusing on the above, we proceeded to a four-day exploratory analysis of indigenous activism during the iNova SmartDataSprint. We take such exploratory analyses as a starting point for potential future, ongoing studies with the same datasets. The main goals are i) to offer a comprehensive methodology to study the emerging clusters in indigenous activism in Brazil, and ii) to investigate how the emergent indigenous activism influences/changes/impacts digital activism as a whole: what are its contributions to social activism practices and literature?

As for the scope of this report, we will focus on the description of the exploratory analysis: the first findings as a direct result of the SmartDataSprint experience.

Query Design & Visual Protocol

In this step, we take into account all posts associated with the hashtag #povosindigenas. The research design was based on the choice of hashtag by indigenous profiles on the platforms.

Methodology

The Dataset

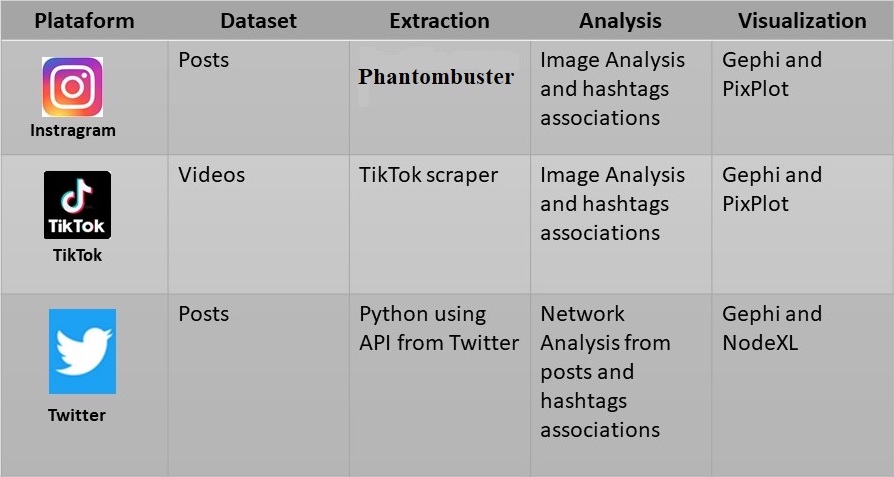

We collected data from TikTok (591 posts, 17 April 2020 – 03 February 2022); Instagram (4,939 posts, 21 May 2018 – 02 February 2022); and Twitter (37,731 posts, 01 February 2018 – 31 January 2022). Data extraction was performed based on the query #povosindigenas (Omena, Rabello and Mintz 2020), biassing the analysis to narratives by and about indigenous peoples and, therefore, including a good portion of indigenous profiles.

We also used a manual cross-platform analysis to find networks from each platform. The selection of influential pages and profiles for data collection was a result of a previous analysis on the Environmental Agenda in Brazil, held by FGV DAPP’s researchers, based on data from Twitter and Facebook groups from 1 June to 20 September , 2021. In this query, we collected all posts available on the three platforms published on/by pages/profiles from 124 indigenous influencers, indigenist organisations and associations dedicated to the indigenous peoples’ agenda (see the full list here: link). Figures 1, 2 and 3 show the most popular posts related to the hashtag #povosindigenas on Instagram and TikTok.

Figure 1: Most popular posts on Instagram from the query: #povosindigenas. Source: Print screen from Instagram.

Figures 2 & 3: Most popular posts on TikTok from the query: #povosindigenas. Source: Print Screen from TikTok.

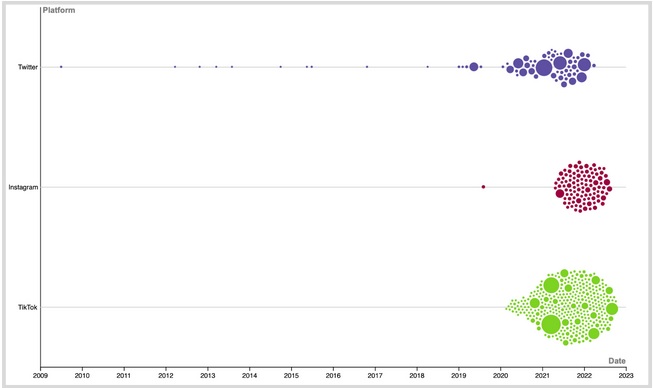

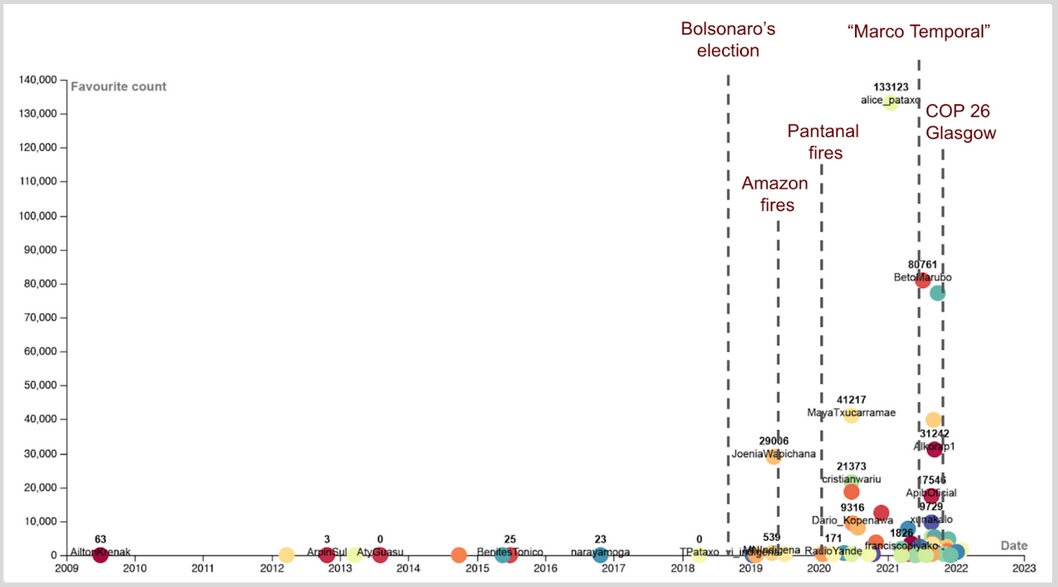

Figure 4 summarises the post distribution over time, per platform. Note that the thematic hashtag gained prominence in mid-2019, the very first semester of Jair Bolsonaro’s administration, which was marked by national and international controversy related to environmental policies and divisive claims on indigenous peoples. The data dominance shifts from Twitter to TikTok’s in early 2021, though such networks have been ongoing since 2020 on the latter platform.

Figure 4: Sample posts distribution over time on Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok. Data viz: Mattia Mertens

Methods

As every methodological choice has an impact on the results found, we aimed to build a mixed-methods (i.e. qualitative and quantitative) analyses of indigenous activism on TikTok. On the one hand, extending our analysis beyond this platform by building a cross-platform analysis, and on the other hand, collecting information related to the accounts and profiles of indigenous influencers that revealed the use of hashtags to enhance their posts. For data extraction, we used the Phantombuster software to collect data from Instagram, based on the hashtag query #povosindigenas. For Twitter data, we used the tool NodeXL, which relied on the platform’s API with the hashtag as a collection parameter. In the case of TikTok, we used a TikTok scraper to collect information based on the same hashtag.

To answer our first research question (How do indigenous influencers engage with the audience on TikTok, Twitter and Instagram?) we sought to make a qualitative analysis from the accounts of indigenous influencers. Based on this information, we detected that some hashtags were recurrent, as in the case of #povosindigenas, and thus we established our standard for data collection from the hashtag.

Within a cross-platform analysis perspective, we collected data from Twitter, Instagram and TikTok from the same profiles of indigenous influencers, based on the aforementioned hashtag. From this point on, we identified that, on each platform, a different type of communication resource was used: on TikTok, some more recurrent trends on the platform were used; on Twitter, posts of a political-institutional nature were published; while on Instagram, campaigns were carried out for causes connected to the environmental and indigenous agenda.

This observed aspect also answers our second research question (What political and social uses emerge from these environments in this context?). However, in this case we used some resources such as an analysis of associations between hashtags through network analysis. The hashtag networks for the #povosindigenas datasets (Twitter, Instagram and TikTok) were constructed on open source software Gephi (Bastian et al, 2009), where the nodes comprise hashtags and users, with edges linking users to hashtags (ie. when a user tweets a particular hashtag, a connection is made between them). The force-directed algorithm OpenOrd (Martin et al 2011) was applied to provide a visual spatialisation of nodes. Nodes and labels were coloured according to their modularity class (Blondel et al, 2008). The size of the labels correspond to their weighted in-degree centrality. Final graphs were filtered for hashtags that appeared at least five times, in each dataset.

Word clouds for the #povosindigenas datasets (Twitter, Instagram and TikTok) were constructed on open source web application Voyant (Sinclair and Rockwell, 2016). Corpora were created with the text from each dataset, which were imported into the application. The tool “Cirrus” was applied to visually display the 500 most frequent words in each corpora. The most frequent words are placed centrally and sized the largest. Colours and absolute positions of the words are not significant.

Distinctive words for the #povosindigenas datasets (Twitter, Instagram and TikTok) were also determined on Voyant. Among other metrics, the “Summary” tool displays the most distinctive words in each dataset, compared to the rest of the corpus.

When trying to answer the third research question (What are the trending thematics on each analysed platform?), the research employed tools such as: Gephi ( already mentioned), NodeXL (with a primary focus on Twitter data), and image analysis for TikTok and Instagram posts. In the visual image analysis of TikTok posts, we divided the dataset into some categories: Naturalistic, Portraits, Half body, Women, Group of people, Text based, Close up shots, Traditional headpiece, Screenshots, and Empowering messages. We also did the same visual image analysis on Instagram posts, dividing the data into the following dimensions: Text Based and Environment.

Our findings suggest that the platforms’ unique combination of hashtags allow indigenous and indigenists profiles to drive affective content and engage in overlapping and interconnected conversations about advancing the environmental agenda, emerging key themes as the centrality of the indigenous activists in the discourse and the political nature of such networks.

Indigenous profiles have protagonism in the debate

In our analysis of the features used by our sample’s users for political messaging, we found clues to the centrality of indigenous digital activism in the political debate of the 21st century, with the environmental issue at the heart of the discussion. In this way, we found parallels with a recent study developed by DAPP within the scope of the digital public debate and the green agenda (RUEDIGER et al. 2021). The study pointed to the protagonism of indigenous agendas in the environmental debate in the period studied, driven by indigenous profiles and indigenist institutions, a discussion that generally takes place among scientists and journalists (RUEDIGER et al. 2021, 17).

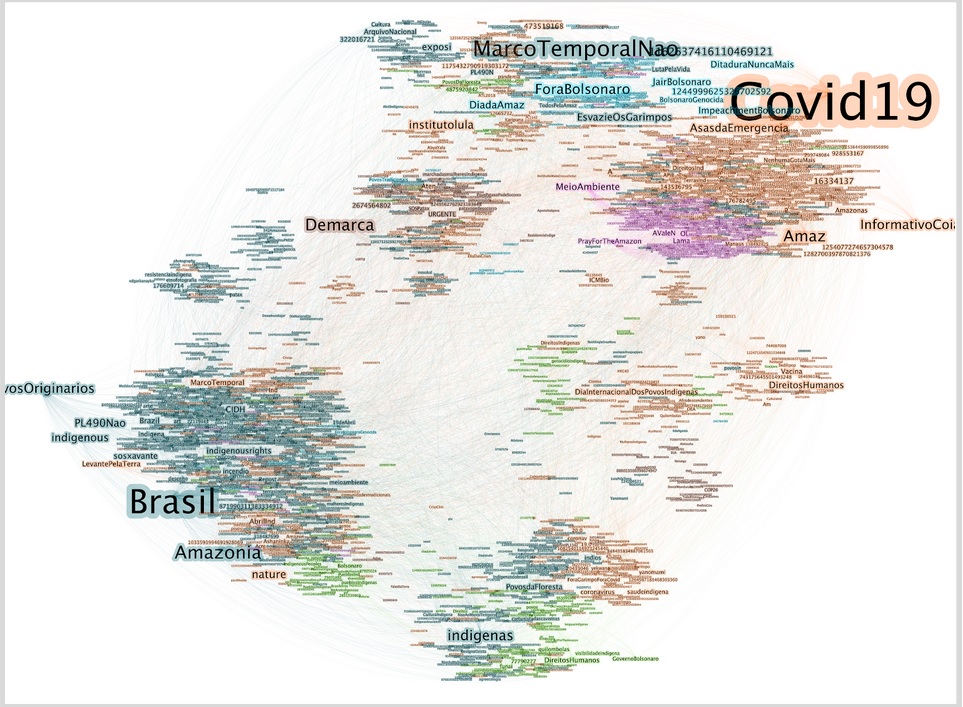

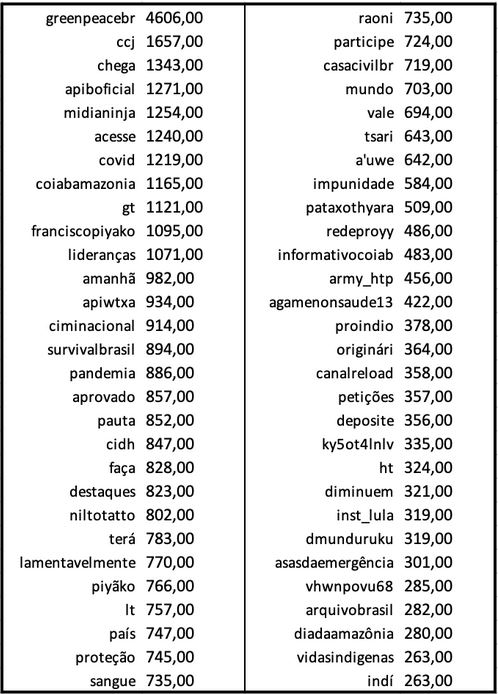

On Twitter, the content published by profiles that used the hashtag #povosindigenas addressed more generalist topics, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, the issue of the environmental crisis in the Brazilian Amazon, and the Marco Temporal vote in the Brazilian Supreme Court. In the analysis of the network of hashtags on Twitter, we observed a crossing of indigenous agendas in social demands, latent in the current period (2022), such as the pandemic crisis and the protection of the Amazon, critical points with wide international repercussions under the administration of President Jair Bolsonaro, as we discuss in the next section.

Still on Twitter, we analysed the 500 words most frequently used in tweets containing the hashtag #povosindigenas. The graph shows that the posts engage with indigenous profiles, such as that of indigenous leader Sonia Guajajara (@gajajarasonia), the environmental non-governmental organisation in Brazil Greenpeace (@greenpeacebr), the abbreviation of retweet (rt), and themes related to the indigenous struggle for the protection of the Amazon and its territory in the Brazilian context and the Covid-19 crisis, confirming the trend towards the protagonism of indigenous causes and a possible connection to environmental and social issues.

Figure 5: Network of hashtags from Twitter #povosindigenas dataset. Includes only hashtags that appeared at least five times. Force directed algorithm OpenOrd applied for spatialization of nodes, colours by modularity class. Tool: Gephi. Hashtags: 782. Data viz: Bia Carneiro.

Figure 6: Word cloud for 500 most frequent words in Twitter #povosindigenas dataset. Tool: Voyant. Data viz: Bia Carneiro.

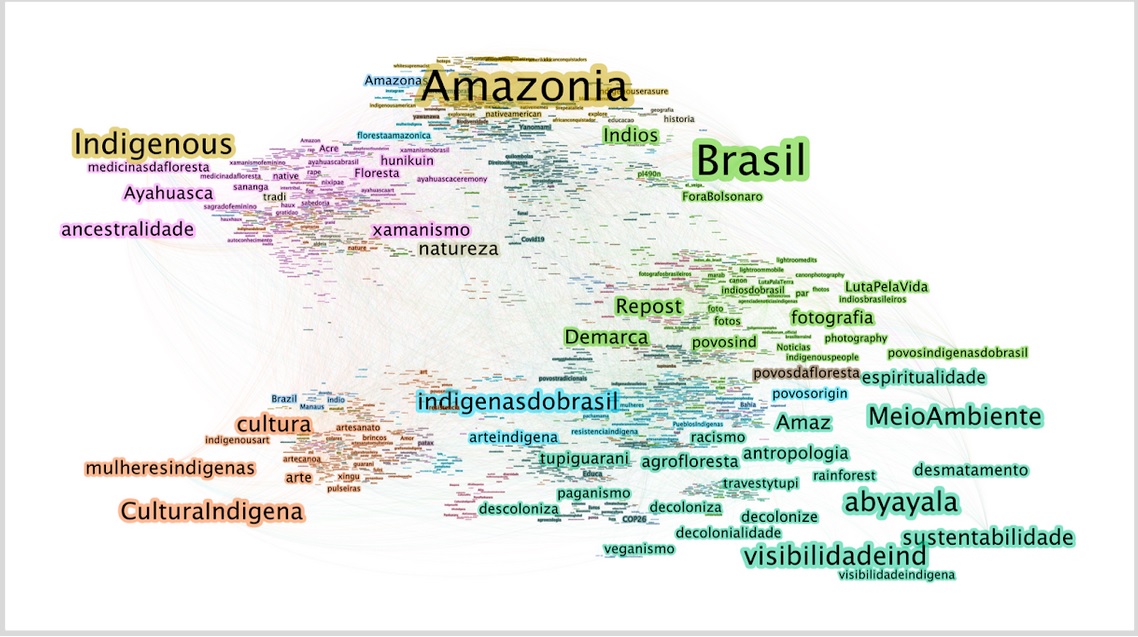

Furthermore, we observed the ambiguity of indigenous issues messages and their connections with intertextual and cultural factors to make meaning. We found, for instance, that profiles on Instagram combined the hashtag #povosindigenas with a variety of topics related to Amazonia, indigenous culture, racism, veganism, sustainability, decoloniality, and so on. The discourse, often political and ideological, makes it difficult to analyse whether these become popular due to the seriousness of the issues or if it involves other conditions, such as fun or visibility.

Figure 7: Network of hashtags from Instagram #povosindigenas dataset. Includes only hashtags that appeared at least five times. Force directed algorithm OpenOrd applied for spatialization of nodes, colours by modularity class. Tool: Gephi. Hashtags: 761. Data viz: Bia Carneiro.

Figure 8: Word cloud for 500 most frequent words in Instagram #povosindigenas dataset. Tool: Voyant. Data viz: Bia Carneiro

Indigenous networks are quite political

The research follows the understanding that the appropriation of techno grammatical uses applied to communicational and political strategies in digital social networks has generated significant impacts that are not restricted to these digital environments. When taking into account the Brazilian context, to which the research is limited, it is possible to identify, in its most recent political conjuncture, a greater mastery of these resources and, therefore, greater visibility and political strength of leaders and groups identified with right-wing and conservative ideologies. After the election of the current president Jair Bolsonaro, a candidate with an inexpressive party structure, but who managed his campaign primarily based on social networks, this advantage is consolidated and reaches the institutional space.

Despite this, opposition groups and leaders have increasingly invested in technical training, cooperation, and empowerment networks on digital platforms. Indigenous leaders and groups have been exemplary in the way they have articulated their agendas (issues) and political actions, making use of the potential of social networks, attracting allies but maintaining a leading role in addressing their issues, pressure tactics, and policy implementation.

In this perspective, the analysis reinforces that indigenous and indigenist profiles have been the biggest references and the central sources of the debate around their causes, that is, the profiles of indigenous organisations and indigenous leaders are consolidated as legitimate representatives of their struggles, associated with traditional and alternative media vehicles, and ally profiles — in general actors of institutional politics on the left of the political spectrum —, which strengthen the political engagement and the visibility of their actions. The ongoing monitoring of the public debate on emerging topics that reach the public spheres indicates that it is an atypical configuration on the platform broadly, where influencer profiles commonly form clusters around themselves on any emerging topics.

Different perspectives on both networks — created around the hashtag #povosindigenas or the selected profiles/pages — point to two characteristics, in terms of topic coverage: the diversity of thematics (following the same trend identified on the Brazilian environmental agenda as a whole, see RUEDIGER et al. 2021) and the political nature of such networks. We analysed time series, social graphs, hashtags, distinctive words and word clouds to have a sense of the contents circulating within these networks, as we show in this section.

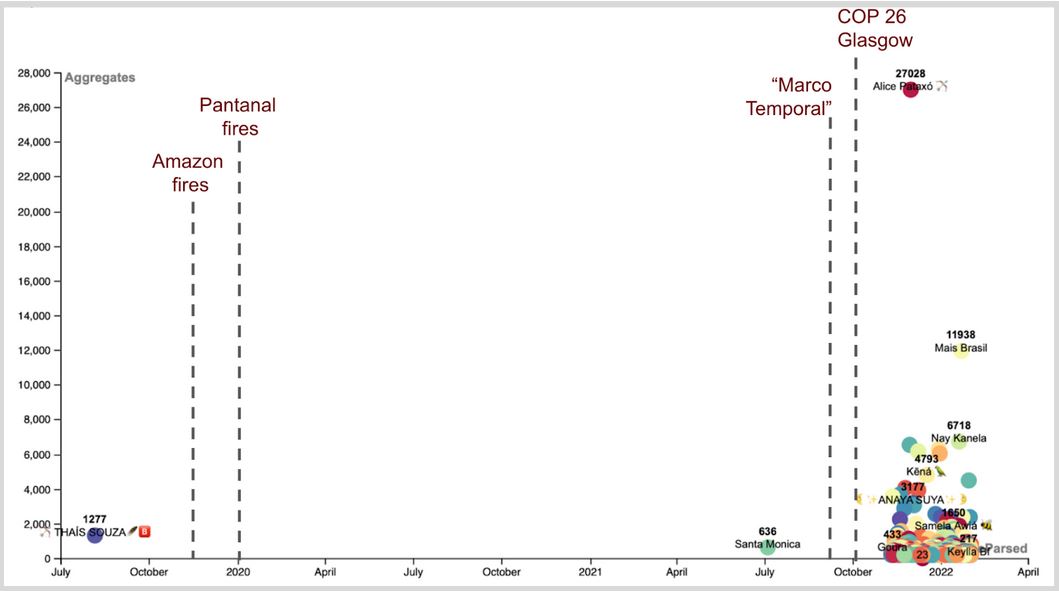

As previously mentioned on fig. 4, the analysed networks emerged in mid-2019, the first year of Bolsonaro’s administration. Figs. 9 and 10 should be seen in this context too. They show the post with the highest engagement from each selected influencer (indigenous persons, indigenist organisations or associations linked to indigenous peoples’ agenda) respectively on Twitter and Instagram. They show that the fires in the Amazon forest and the Brazilian Pantanal were responsible for peaks of engagement in mid-2019. At that time, the federal administration’s inertia and a number of controversies involving both President Bolsonaro and Minister of the Environment Ricardo Salles helped to aggravate the environmental crisis. Seen in conjunction, figs. 4, 9 and 10 suggest that the particular approach of the Brazilian government to the environmental agenda may have helped to foster indigenous activism online.

Other political events were also prominent such as COP 26 — the United Nations climate conference that took place in November 2021 — and Marco Temporal — a legislative question introduced by the 1988 Federal Constitution that was under scrutiny at the Supreme Court in mid-2021, motivating a strong indigenous mobilisation in the capital Brasília and on social media.

Figure 9: Engagement on Twitter: post with the highest engagement from each selected influencer (indigenous person, indigenist organisations or associations linked to indigenous peoples’ agenda). Data vizz: Mattia Mertens.

Yet, the analysis focused on top-posts only shows a fraction of the content. Seen in isolation, it might confirm the common sense that the indigenous influencers’ agenda are limited to environmental perspectives. Other visualisation methods show otherwise. A simple hashtag analysis, as represented on fig. 11, point to a whole different agenda of mobilisation, such as Covid-19, vaccines, support to the public health system, transgender visibility, political national issues (such as Bolsonaro’s proposal to return to printed votes putting doubts on the electronic votes adopted by Brazil since 1996), international issues (such as the situation in Rojava) and culture (like indigenous cinema). References to other movements are also present, with a highlight to the hashtag #VidasIndigenasImportam, a reframing of the worldly known political hashtag #BlackLivesMatter, this time with the indigenous lives in evidence.

Figure 10: Engagement on Instagram: post with the highest engagement from each selected influencer (indigenous person, indigenist organisations or associations linked to indigenous peoples’ agenda). Period: July 2019 – February 2022. Data viz: Mattia Mertens.

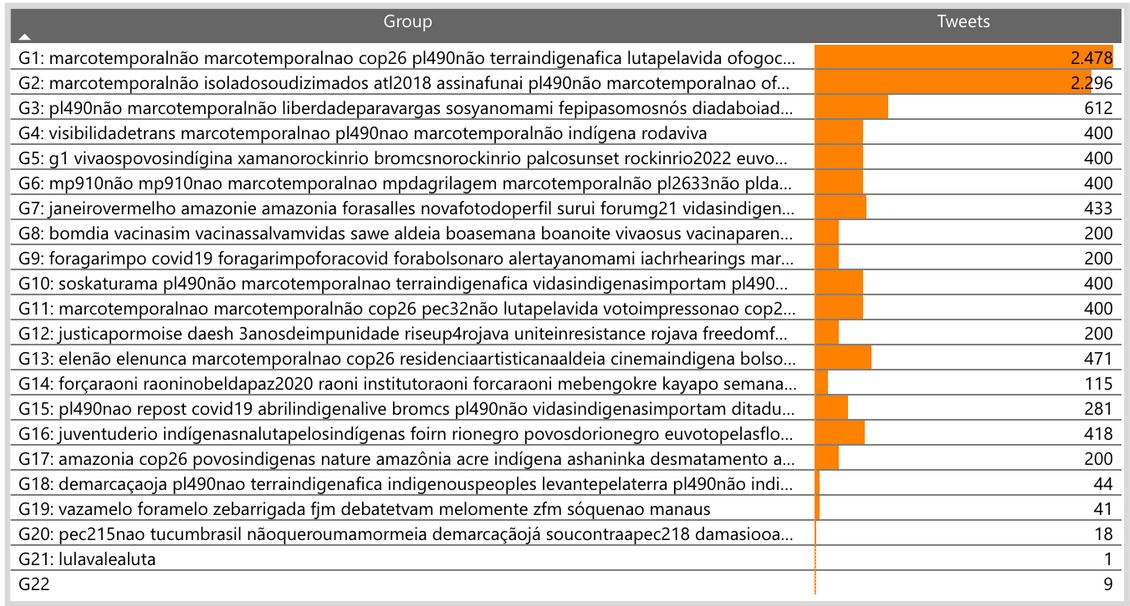

Figure 11: Overview of hashtag frequencies on tweets extracted with the hashtag #povosindigenas. Tool: NodeXL. Data viz: Harald Meier.

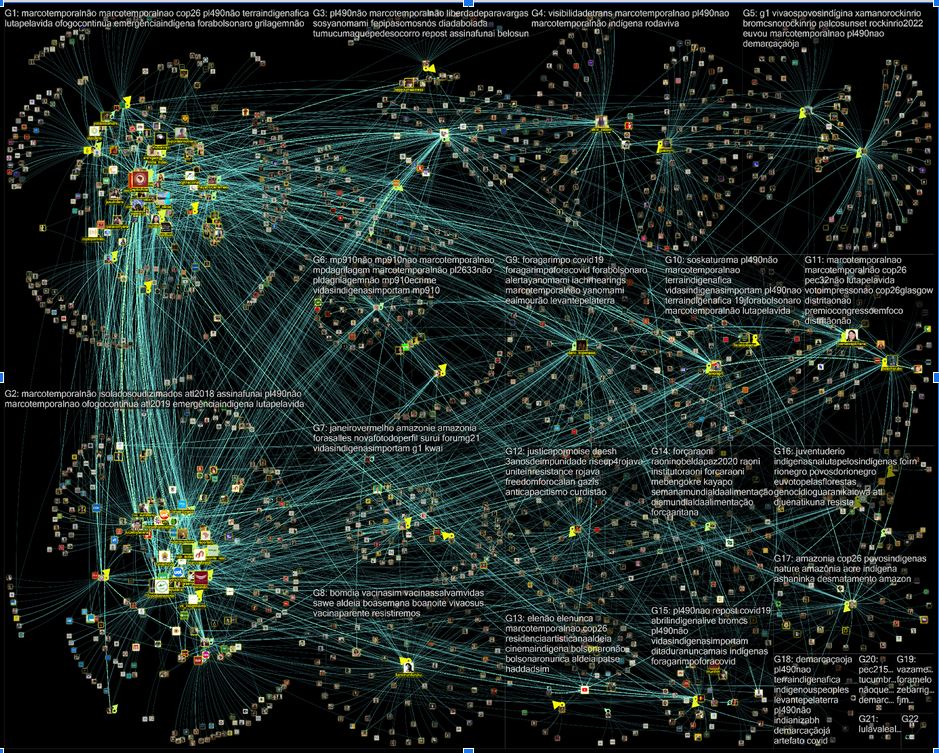

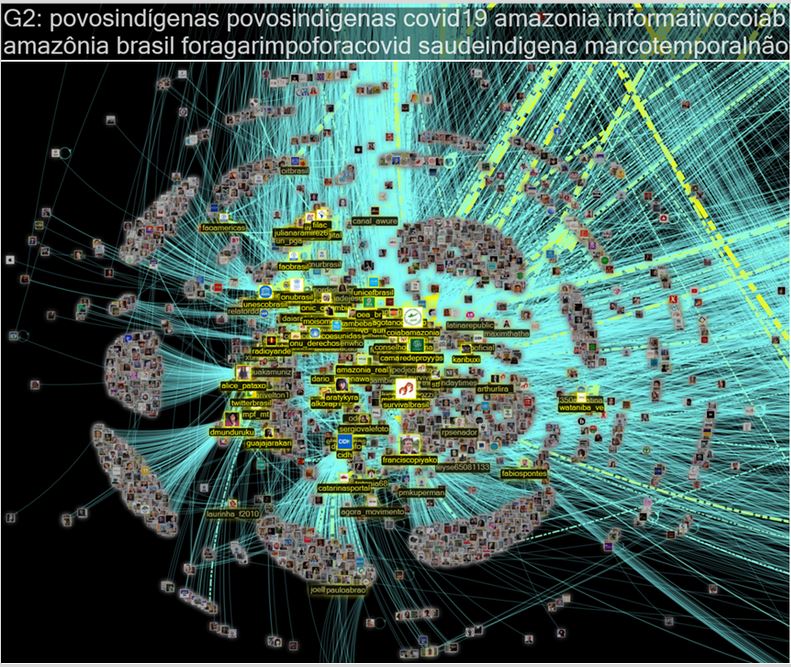

The same hashtags are represented on fig. 12, this time on a graph visualisation that enables assessing which profiles are prominent in each context suggested by a set of hashtags. The two main clusters (at the top) are committed to the Marco Temporal thematic, as also shown on figure 11. While cluster 1 highlights indigenist groups/organisations and individual indigenous influencers, cluster 2 gathers a number of media groups — commercial, independent and locally-based within the Amazon area -, governamental profiles (such as the pro-indigenous organisation Funai) and other indigenist organisations.

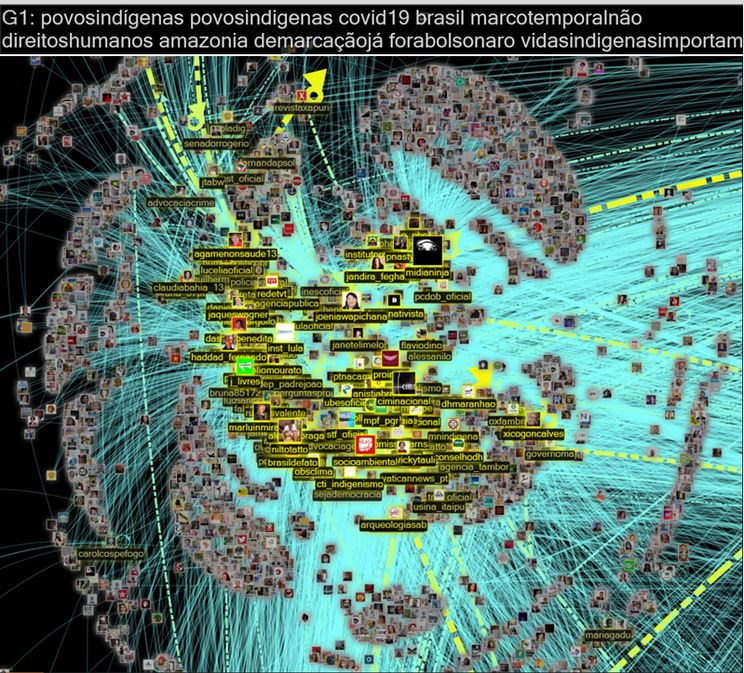

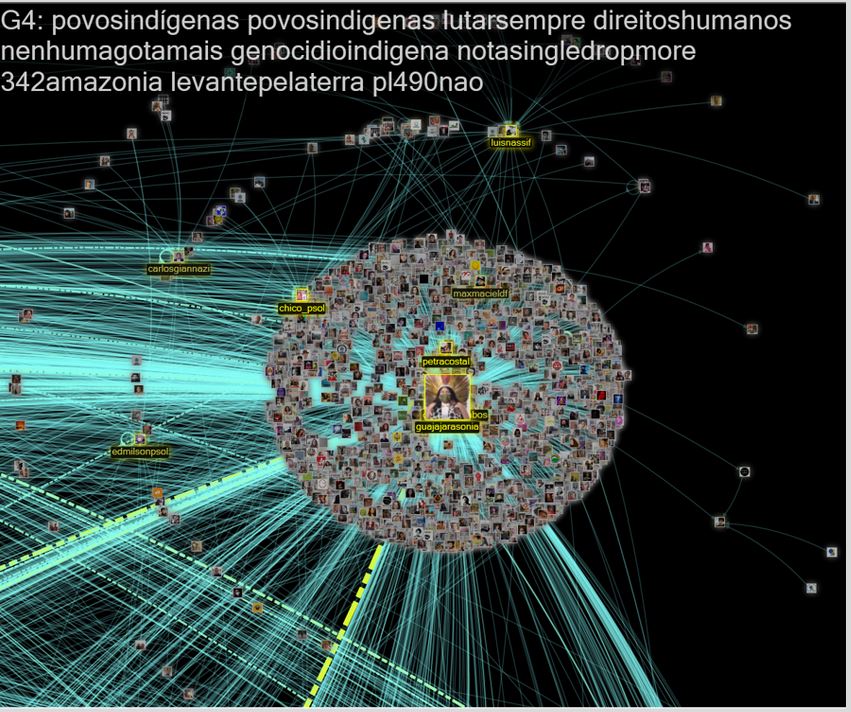

We also used NodeXL to explore social graphs based on the hashtag #povosindigenas. The resulting graph has a different configuration though some of the same hashtags and profiles emerge, as compared to the graph on fig. 12, which was based on the list of selected influencers. The four main clusters from #povosindigenas network are represented on figs. 13 to 16.

Among the most influential participants on cluster 1 (fig. 13) are the first indigenous deputy in Brazil Joenia Wapichana, the official profile for the mobilisation on the Marco Temporal agenda Mobilização Nacional Indígena, and a number of organisations linked to the indigenous and/or environmental agenda like Cimi Nacional (Missionary Indigenist Council), Pro Indio Commission, Centro de Trabalho Indígena (Indigenist Work Centre), Observatório do Clima and SocioAmbiental. Among cluster 1’s influencers are also the long-established national deputy Jandira Feghali, Maranhão state Governor Flavio Dino, the Workers’ Party politicians Benedita da Silva, Fernando Haddad, Senator Jaques Wagner and the former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the Institute Lula, independent newswires such as Agência Pública, Brasil de Fato and Agência Tambor, a trade union confederations’ TV Rede TVT, the grassroots channel Mídia Ninja and the actress Lucelia Santos.

Figure 12: Twitter cluster visualisation based on the list of profiles of indigenous influencers, indigenist organisations and associations linked to the indigenous peoples’ agenda. Tool: NodeXL. Data viz: Harald Meier.

Cluster 2 (fig. 14) seems to be a bridge linking a quite institutional cluster 1 to a diversity of original peoples, represented by a number of individual indigenous profiles such as the content producer Renata Tubinambá, Alice Pataxó, Daniel Munduruku, Kari Guajajara and Alessandra Kopap Mdk. These five examples illustrate the diversity of native peoples involved in the debate, where each “last name” is actually the name of their peoples. Besides individual influencers, cluster 2 also highlights the presence of independent local newswires like the indigenous Rádio Yandê and the Amazon-based news agency Amazônia Real, besides UN Brazilian branches such as ONU Brasil, Unesco Brasil and FAO Brasil.

Clusters 3 and 4 from the #povosindigenas network are much more centralised, with just a few protagonist profiles — many of them from the arts scene. Highlights from cluster 3 (fig. 15) are Greenpeace BR, the artists Gilberto Gil and Daniela Mercury, the DJ Alok, the official profile of the movie A Última Floresta and the influencer Paulo Santiago. As for cluster 4 (fig. 16), the main influencers were the activist Sonia Guajajara and the cinema director Petra Costa.

Figure 13: Zoom in for details on cluster 1 on a twitter visualisation based on the hashtag #povosindigenas. Tool: NodeXL. Data viz: Harald Meier.

Figure 14: Zoom in for details on cluster 2 on a twitter visualisation based on the hashtag #povosindigenas. Tool: NodeXL. Data viz: Harald Meier.

Figure 15: Zoom in for details on cluster 3 on a twitter visualisation based on the hashtag #povosindigenas. Tool: NodeXL. Data viz: Harald Meier.

Figure 16: Zoom in for details on cluster 4 on a twitter visualisation based on the hashtag #povosindigenas. Tool: NodeXL. Data viz: Harald Meier.

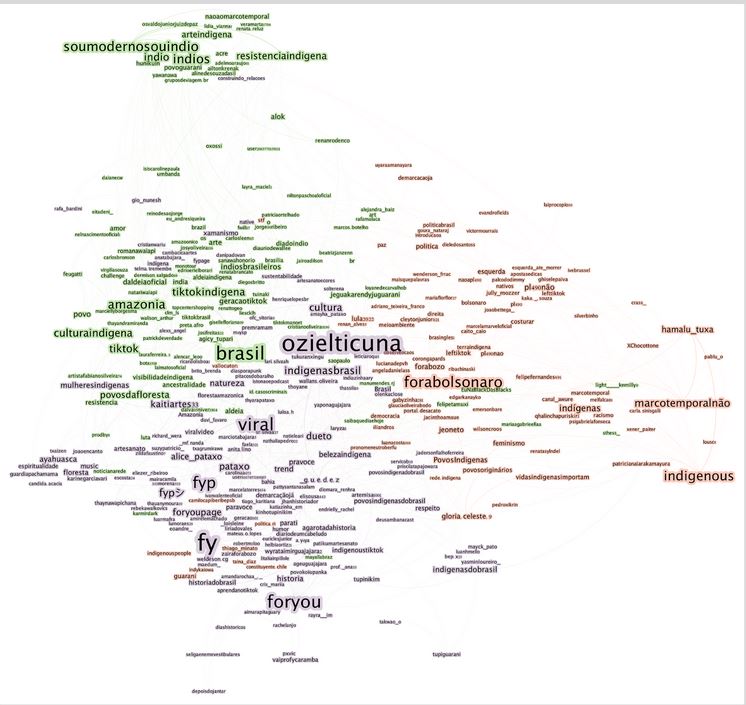

On TikTok, the hashtag analysis also points to the political nature of #povosindigenas networks: even though the platform is known for its entertaining short videos, political content is a highlight, as shown by hashtags like #ForaBolsonaro, #MarcoTemporalNão, #ResistenciaIndigena and #SouModernoSouIndio (fig. 17).

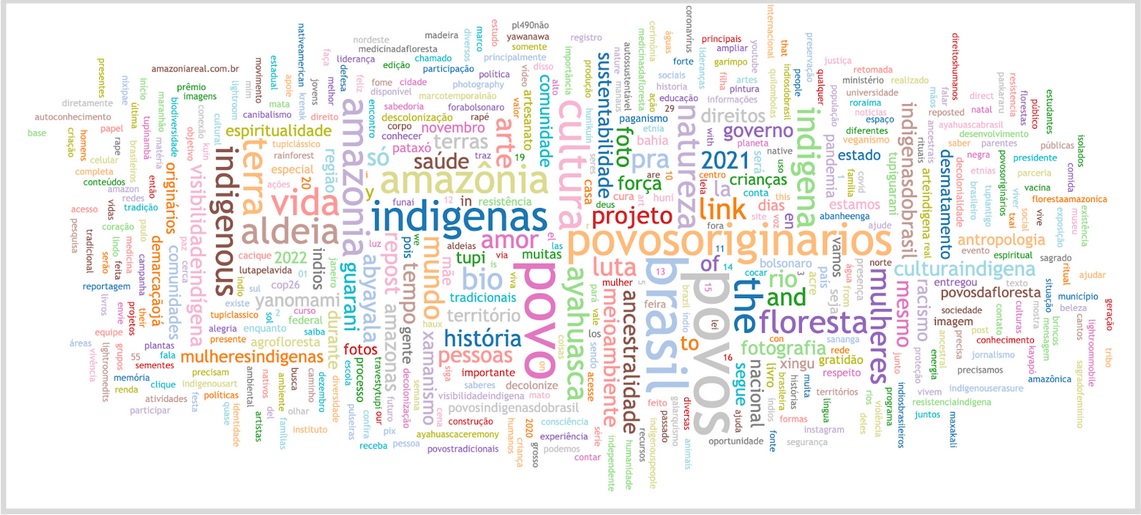

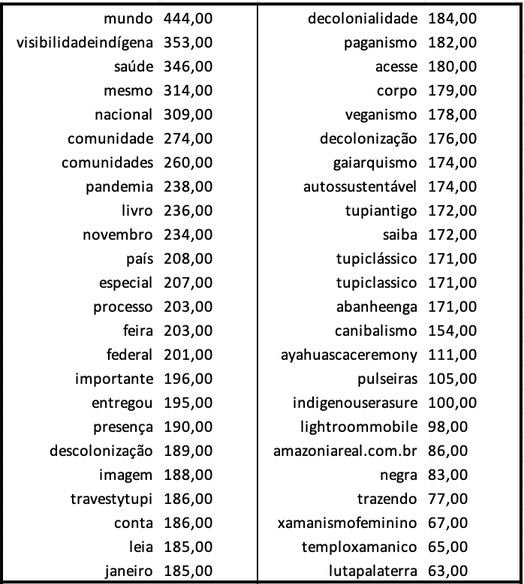

An analysis of the distinctive words within #povosindigenas corpus on Twitter (fig. 18), Instagram (fig. 19) and TikTok (fig. 20) suggests that Twitter is a more political platform for indigenous mobilisation on social media and also a window to give visibility to petitions and calls for action. In contrast, Instagram is more likely to deliver cultural contents — frequently with a political position too, that reinforces proudness of indigenous peoples’ traditions. Words like decoloniality, decolonialism, paganism and indigenous visibility give a sense on how showing their own culture and traditions has an embedded political nature. The expression “sou moderno sou índio” (I am modern I am indigenous), frequent on TikTok, has a similar objective of reaffirming the indigenous culture, identity and potentials.

Figure 17: Network of hashtags from TikTok #povosindigenas dataset. Includes only hashtags that appeared at least five times. Force directed algorithm OpenOrd applied for spatialisation of nodes, colours by modularity class. Hashtags: 118. Period: 17 April 2020 – 03 February 2022. Data viz: Bia Carneiro.

Figure 18: Distinctive words on #povosindigenas Twitter corpus.

Figure 19: Distinctive words on #povosindigenas Instagram corpus.

Figure 20: Distinctive words on #povosindigenas TikTok corpus.

Before pointing out the ways in which different uses on different platforms can generate distinctive behaviours and, therefore, political effects, it is important to highlight the complexity and diversity of possible analytical configurations that involve the relationships of social actors in digital structures. The multiplatform perspective was chosen to identify behavioural patterns and communication strategies based on the distinctive characteristics of each social network. For this reason, the broader objective of this research was to explore how the engagement of certain audiences and social actors is shaped by the uses, content, and affordances that characterise each of the analysed platforms.

The political uses provided by these environments come in a variety of possible forms. For instance, Twitter is identified as a platform that highlights prominent figures of public opinion, but also a space for political organisation, which has influenced contemporary collective action. Instagram, in turn, generally has a strong presence of celebrities, and for political purposes, they often increase engagement and therefore reach audiences for causes to which they adhere.

Tik Tok has been regarded as a network that facilitates cross-cutting political talks. That is, through posts often focused on everyday lives, with emphasis on audio-visual content, politically organised groups have guided their issues and struggles, reaching and sensitising audiences in a broader way. Although social networks can favour the emergence of soft leadership presupposing a horizontal space, in the indigenous case, the organised struggle based on traditional leaders has set the scene and oriented the political dispute of this group. Therefore, through their own understandings and interpretations of political processes, making use of the affordances that favour cross-cutting communication, attracting a greater number of allies, indigenous leaders and groups have been legitimate protagonists of their own causes on the platforms.

It is interesting to note how some profiles are very influential on TikTok, but by comparison they have few followers on other networks. In this sense, the analysis of TikTok allowed us to perceive a network of indigenous activism with a vast connection between them — from the use of hashtags — that seek to place the indigenous agenda as the main target of their posts, appropriating the repertoire of each platform and structuring in a planned way its communication with users.

With regards to engagement, we observed not only the development of the indigenous agenda over time, but also how the actors were involved in it. We can clearly see that Twitter is much more influencer oriented, with few people but with a very high engagement rate, whereas TikTok makes topics more viral: many more people talk about them even if they have a small audience.

Reflections

FGV DAPP is a research centre dedicated to monitoring and analysing public debates related to a broad social and political agenda. Investigating a network such as indigenous activism — especially at a time of polarisation and extreme political grounds in the Brazilian scenario — is more challenging than usual. Our first concern is how to reflect on the indigenous peoples’ agenda from a non-indigenous perspective, in the context of digital research. We are deeply concerned about avoiding common mistakes such as patriarchal, imperialist and invasive perspectives, and that demands a constant process of reflecting and rethinking about objectives and approaches. Questions like “should we avoid highlighting particular profiles and names?” and “Which is the best word to say what we mean?” are frequently on the table. For future work, we have been considering how we can partner with indigenous researchers to go further in this work in a manner that establishes a win-win relationship.

Future Work

During the SmartDataSprint, we made a few experimentations on image clustering with PixPlot. Though we did not get the chance to explore it further during the event, it is part of our current approach to discuss digital methods potentials for indigenous activism on social media. As our text analyses on Twitter, TikTok and Instagram clusters advances, we are able to better understand the data to explore image clusters — typically more challenging to analyse and interpret.

Our goal is to get a better understanding on how to apply a cluster cross-analysis by analysing both text and image clusterings together — that is, as complementary perspectives, not separate analyses. Fig. 22 shows a preliminary view of image clusters based on posts collected from TikTok. The image clustering technique is based on similarities that the algorithm finds on the images such as pixel distribution, colours and elements seen in the frame. Based on that, the algorithm found 10 clusters, represented on figs. 23 to 32. Our future work includes a semiotic analysis of such clusters, seeking clues and short paths to comprehend such grouping in conjunction with the text analysis results.

Figure 22: Image cluster visualisation with pictures from TikTok. Tool: PixPlot. Data viz: Mattia Mertens.

Figures 23 to 32: TikTok image cluster visualisation: details per cluster. Tool: PixPlot. Data viz: Mattia Mertens.

ABIDIN, C. (2021). From ‘Networked Publics’ to ‘Refracted Publics’: A Companion Framework for Researching ‘Below the Radar’ Studies. Social Media + Society, 7 (1): 1–13. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120984458.

BANET-WEISER, S. (2012). Authentic™: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture. New York: NYU Press.

BASTIAN, M., HEYMANN, S. & JACOMY, M. (2009). Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

BLONDEL, V.D., GUILLAUME, J.-L., LAMBIOTTE, R. & LEFEBVRE, E. (2008). Fast unfolding of communities in large networks, J. Stat. Mech., P10008.

CHUN, W. H. K. (2021). Discriminating Data: Correlation, Neighborhoods, and the New Politics of Recognition. 1st ed. MA: MIT Press.

ENLI, G. (2015). Mediated Authenticity: How the Media Constructs Reality. Peter Lang. New York: Peter Lang US. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3726/978-1-4539-1458-8.

HAUTEA, S., PARKS, P., TAKAHASHI, B. & ZENG, J. (2021). Showing They Care (Or Don’t): Affective Publics and Ambivalent Climate Activism on TikTok. Social Media + Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211012344

MANSANI, T. (2022). Jovens jornalistas indígenas combatem fake news na Amazônia. Brasil de Fato. 08 de Fevereiro de 2022. Available at:

MARTIN, S., BROWN, W. M., KLAVANS, R. & BOYACK, K. (2011). OpenOrd: An open-source toolbox for large graph layout. SPIE 7868, Visualization and Data Analysis, San Francisco Airport, CA, USA.

NAKAMURA, L. (2014). Indigenous Circuits: Navajo Women and the Racialization of Early Electronic Manufacture. American Quarterly, 66 (4): 919–41. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2014.0070.

RUEDIGER, M.A., GRASSI, A., Dienstbach, D., SANCHES, D., SILVA, L. R. da, CANAVARRO, M., CORDEIRO, M. S., BARBOZA, P., ALMEIDA, S. & PIAIA, V. (2021). The public digital debate and the green agenda: emergent topics in the Brazilian environmental debate. Policy paper. Rio de Janeiro: FGV DAPP.

SINCLAIR, S. & ROCKWELL, G. (2016). Voyant Tools. Web. http://voyant-tools.org/.

TURKLE, S. (1995). Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. 1st ed. New York: Simon and Schuster.