Project title: #homesofInsta for a #lockdownlife: a digital exploration of everyday aesthetics and mediated domesticity on Instagram

Project leaders: Sofia P. Caldeira & Sander De Ridder

Team Members: Ana Marta M. Flores, Erec Gellautz, Federico Pozzi, Hantian Zhang, Mariah Nikolic, Mengying Li

Project pitch slides

Final presentation slides

Key Findings

Introduction

Research Questions

Query Design & Visual Protocol

Methodology

Findings

Discussion

References

This project centred a digital exploration of the visualities and aesthetics of mediated domesticity on Instagram in times of Covid-19. We explored four different hashtag clusters, representing different facets of the collectively constructed idea of domesticity and, particularly, the home in the context of a pandemic-induced lockdown.

Although each hashtag cluster offered particular insights, as will be explored further in this report, the key findings of this project illustrate how the photographic content present in these hashtags can be clearly divided between highly aestheticised content and more quotidian and less aestheticised content. While highly aestheticised content (i.e. content with high production values and following the dominant cultural scripts of Instagram [Abidin, 2016]) was especially noticeable in popular or highly engaged with posts, as well as in well-established thematic hashtags like #homesofinsta, #realhomesofinstagram, or #homesweethome, less aestheticised content was predominant amongst low engagement posts, produced mainly by ‘ordinary’ users, thus showing a less curated vision of the home.

Despite Instagram’s cultural imaginary being commonly associated with photographic, and later video, content (Manovich, 2017; Leaver, Highfield & Abidin, 2020), it was also noteworthy the amount of graphic content (mainly of commercial nature or in meme-like formats) that was shared and re-shared on these hashtags.

While this project offers only a limited entry point into this research topic, it illustrated the ways in which different types of visualities coalesced within Instagram hashtag cultures to create a multi-layered idea of the home and domesticity. The home on Instagram becomes a floating signifier (Barbour & Heise, 2020), carrying multiple meanings as both a real-life photographable experience, an inspirational goal to be emulated, or even a graphic representation offering an imagined alternative or a satirical escape to our ‘real’ experience of the home during quarantine.

This project relies on a digital exploration of Instagram and its aesthetics of mediated domesticity in times of Covid-19. The on-going Covid-crisis has changed our experience of the home, through multiple lockdowns and calls from transnational health organisations to stay home and self-isolate to slow down the spread of the virus (Kay, 2020). In this context, social media, amongst it, Instagram, has gained an ever-more central role, being widely used as both a source of socially-distanced interactions, an escape from the boredom of confinement (Hermes & Hills, 2020), a source of pandemic-related communication and news, and an archive of the mediated aesthetics of the unfolding crisis (Prins, 2020).

The pandemic collapsed different facets of life into the domestic space – downtime and leisure, sociality, education, and particularly work-life, as telework became the norm for many professionals. The home was forced into the centre stage of everyday life, inevitably becoming also one of the main backgrounds for Instagrammable photo-ops. This came to emphasise the already noticeable importance of everyday aesthetics and mundane contexts on Instagram (Caldeira, De Ridder & Van Bauwel, 2020).

This project focused on the analysis of the diverse visualities and aesthetics of domesticity that co-exist within Instagram, as these can be revealing of wider socio-cultural and economic structures. This analysis highlighted the tensions that are subjacent to these social media platforms, between idealisation, careful curation of images of domesticity and self-branding, on one hand, and the drive for authenticity and relatability, on the other (e.g. Banet-Weiser, 2012; Marwick, 2013).

This research departed from the broad research question: How is the home and domesticity represented on Instagram in the context of the current Covid-19 crisis and its lockdowns?

This question served as a starting point for the initial digital exploration that was conducted during the Sprint. As the project centred its focus on the exploration of visualities, a set of narrower research questions were formulated and empirically addressed:

- What types of visualities and narratives of the home and domesticity are constructed within different Instagram hashtag clusters?

- Are visualities and narratives different amongst highly-engagement posts and low-engagement posts?

- What type of actors dominate the high-engagement posts?

Query Design & Visual Protocol

To explore the visualities and aesthetics of mediated domesticity on Instagram, we worked with a set of four hashtag clusters, representing different aspects of the phenomena.

1) General home life / decor / aesthetic hashtags: #homesofinsta; #realhomesofinstagram; #homesweethome

2) Specific Home-Lockdown hashtags: #staythefuckhome; #shelterinplace; #quarantinehouse

3) Pandemic/Lockdown related hashtags: #quarantinelife; #lockdownlife; #quarantinechronicles

4) Work-from-Home hashtags: #homeoffice; #telework; #workingfromhomelife

These hashtags were selected after an initial exploratory qualitative analysis of Instagram. The hashtags were chosen because they expressed a clear connection with the topics of interest, represented a diversity of scope within the topics, and all had a significant number of posts. All hashtags are in English, both for a question of language accessibility and for the transnational scope of use that English, as a favoured language on Instagram, carries (Pearce et al., 2020).

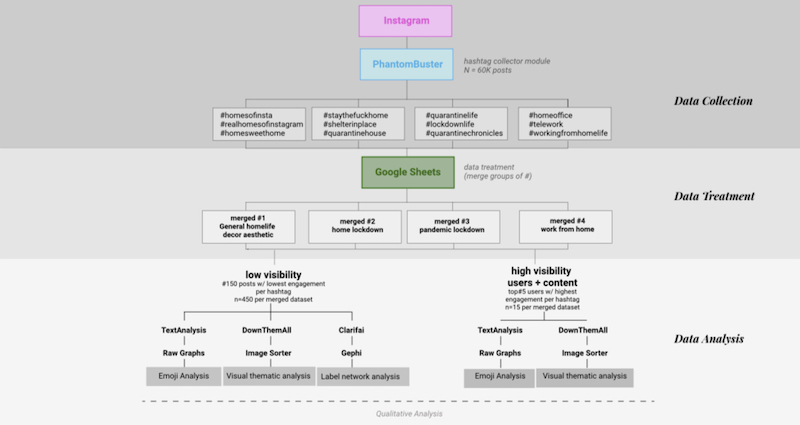

FIGURE 1. Research Design Protocol

The dataset was assembled prior to the Data Sprint, with all hashtags queried and data collected on the 25th of January 2021, to ensure that all image URLs were still active during the Sprint. The dataset was created using the Phantom Buster Instagram Hashtag Collector, querying 5000 posts per hashtag. The images associated with these posts were downloaded during the sprint, using the DownThemAll extension for Google Chrome.

We then cleaned and treated the data, removing duplicates and creating separate Google Spreadsheets for each hashtag cluster, merging the data of the three hashtags contained within it.

On a first stage, we conducted digital exploration of the whole dataset, in order to familiarise ourselves with it. This initial exploration allowed us to engage with different layers of the research object — including hashtag activity, visual content, textual and emoji content, and key actors — thus getting a broader sense of the dynamics contained in the studied hashtag clusters. This initial exploration included the use tools introduced during the Data Sprint, including Google Spreadsheets, ImageSorter, RawGraphs, TextAnalysis, TagCrowd, WordTree, and WordIJ.

After this familiarisation, we narrowed on the analysis of the visual content of each hashtag cluster. The dataset was filtered according to engagement numbers, to divide the analysis between low visibility posts and high visibility users and their content (Omena, Rabello & Mintz, 2020).

For the low visibility posts, we analysed the 150 least engaged posts per hashtag. This amounted to approximately 450 posts per hashtag cluster, totalling circa 1800 posts. The analysis was focused solely on images, as such the final sample of studied images was smaller than the total number of posts selected per cluster (n=450). This was because a small number of posts were either videos (which we were unable to download and would require different tools for analysis) or image posts that were since deleted or changed the privacy settings of their accounts.

For the high engagement, we analysed the top five users with the most total user engagement for each hashtag and all their posts present in the dataset. This amounted to 15 users per hashtag cluster, 60 users in total.

The Engagement was calculated as the sum of a post’s likes and comments. And total user engagement as the sum of all likes and comments of each unique user in each hashtag cluster merged data set.

We explored the visualities of each hashtag cluster in a three-folded way. Firstly, by using ImageSorter to plot all images in accordance to colour, thus allowing us to explore variations, patterns, and repetitions contained in each cluster, and to zoom in on noteworthy patterns. Secondly, we built on this exploration, performing a manual qualitative thematic analysis, using Figma to organise image groups around the dominant themes identified within each cluster. Finally, we complemented these analyses with the creation of a computer vision based image-label networks, automatically tagging the images using Clarifai and using Gephi to create a network for each hashtag cluster.

In addition, we also analysed the emojis most-commonly used for each hashtag cluster. Using the Textanalysis tool we collected CSV-type outputs for all emojis used, creating visualisations for their frequencies per category and per hashtag using RawGraphs and Figma.

1) General home life / decor / aesthetic hashtags | Merged #1

The General home life/ aesthetics hashtag include three hashtags, #realhomesofinstagram, #homesofinsta and #homesweethome.

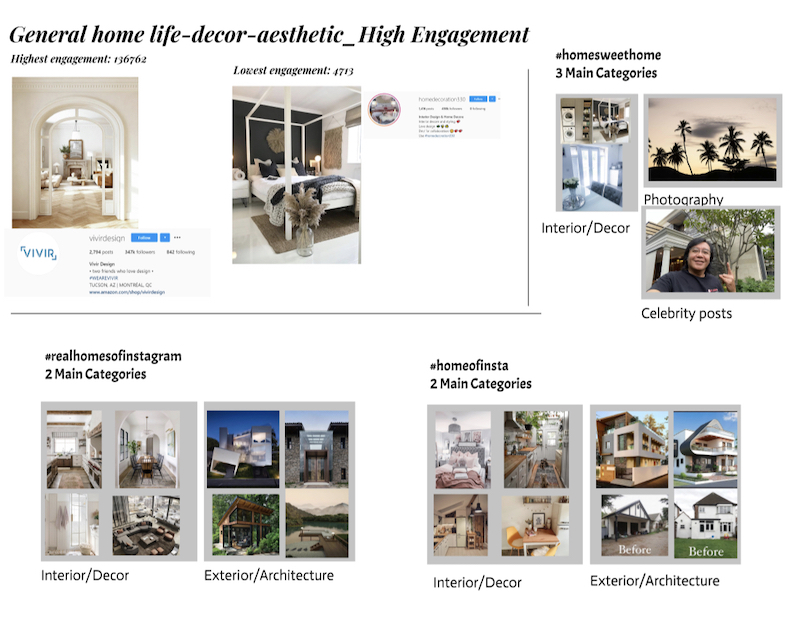

High engagement posts

FIGURE 2. Figma, Manual Thematic Coding

The results showed four main categories among the high-engagement posts (101 images): Décor, Architecture, Photography and Celebrity posts.

Décor posts mainly involve shared images with home decoration and interior design, with details such as the use of colours and specific furniture. Most of the posts seem to be created for marketing purposes, posted by accounts from design agencies or deco companies. There are also some posts by distribution accounts whose main purpose is sharing home décor inspiration.

Architecture involves images of the exterior design of houses. Some of the posts are purely sharing the finished design, while others involve house transformation showing the process through which old houses are renovated. Just like the Décor category, the main accounts that post those images are design companies or account mainly for sharing design inspiration.

There was one post in the high engagement group related to Photography, in which a professional photographer posted a landscape image of their hometown with the hashtag #homesweethome

Finally, the Celebrity Post contains one photo of a famous Indonesian singer with his house.

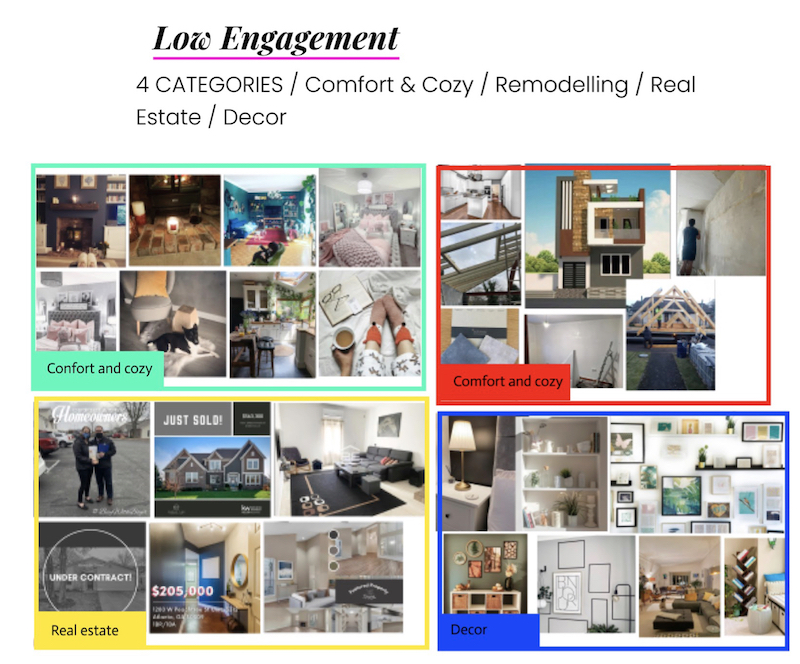

Low engagement posts

FIGURE 3. Figma, Manual Thematic Coding

When it comes to the low-engagement group ( 424 images and 26 videos), we identified four main categories, Comfort & Coziness, Project & Remodelling, Real Estate and Décor.

Comfort & Coziness represents images that show a comfortable environment of a home. Two characteristics seem to merge in this category: the professional interior designed home or a more “down-to-earth” aesthetic of regular homes. Both of these homes present a cosiness energy. The ambience in those images also set by pets, hot beverages and pillows, all assembled to convey a comfy feeling.

Project & Remodelling involves architecture inspiration and small house transformations, similarly to the Architecture category from high engagement posts. It also contains 3D models of the house projects and the renovations in-process which may be related to the current pandemic.

Real Estate includes mostly commercial and marketing content. For example, house selling and buying advertising.

Finally, the Décor category includes general decoration of homes such as wall arts, shelves, lighting, and bookshelves. However, unlike the posts from the high engagement group, the low engagement Décor posts seem to be more authentic, from accounts of regular users, which are not “perfectly photographed”.

Overall, by analysing both high and low engagement groups in the general home life / aesthetic hashtags, we can conclude that these hashtags focus mostly on decor and architecture, regardless of being high or low engagement posts. However, in the low engagement posts, there seems to include more general content, such as comfort and cosy environments, real estate photos, remodelling and authentic décor, especially when compared with the more “aestheticised” posts in the high engagement group.

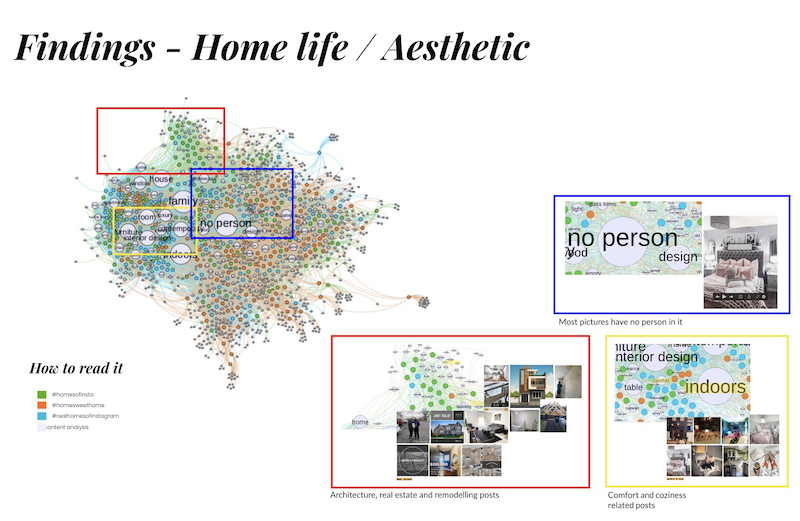

Furthermore, as shown in Figure 4, the visual network showed us that the computer vision also reflected the predominance of certain types of photos in specific hashtags such as the architecture photos.

FIGURE 4. Gephi, Image Label Network. Using Clarifai to automatically generate labels.

2) Specific Home-Lockdown hashtags | Merged #2

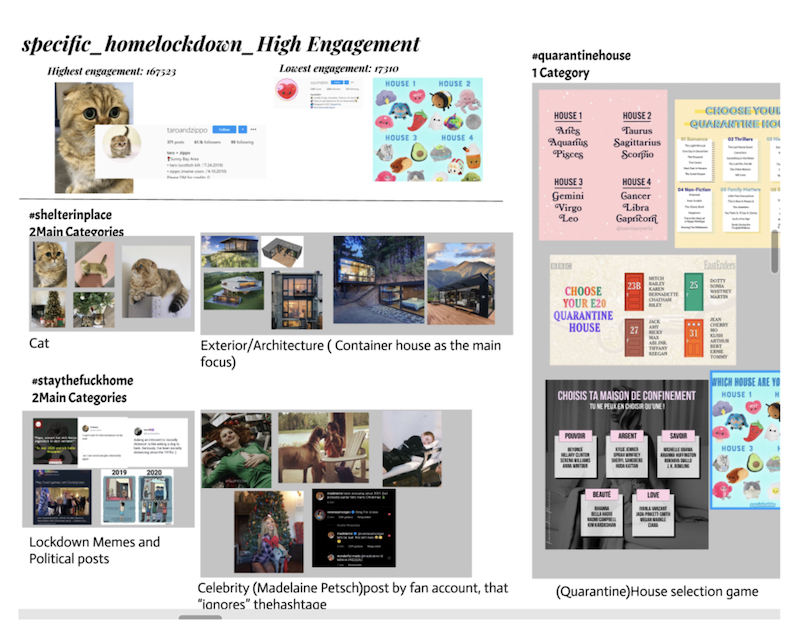

The Specific Home-Lockdown hashtags are #shelterinplace, #staythefuckhome, and #quarantinehouse.

High engagement posts

FIGURE 5. Figma, Manual Thematic Coding

When it comes to high engagement posts (315 photos, 20 videos), 5 categories have been found: Animal, Architecture, Memes, Celebrity Posts and House Selection games.

The Animal posts only from one account which mainly contains photos of two cats under the #shelterinplace.

The Architecture post is similar to the one from the General Home Life/ Aesthetic hashtags with images of architecture/exterior design. However, for the #shelterinplace especially, there are predominant designs of container houses. Those posts are mainly shared by design companies and also accounts for sharing design ideas.

Posts from the Memes category were found under the #staythefuckhome, which mainly contains quarantine/lockdown memes. They are mainly graphical content rather than photos – a combination of images and texts. There is also one political meme regarding Covid posted by an anti-Trump account.

Another category under #staythefuckhome are posts dedicated to one actress, Madelaine Petsch. The account seems to be a fan account and the posts are completely unrelated to the pandemic. However, the hashtag #staythefuckhome was found under the images, alongside a description that asked followers to “ignore the tags”. This perhaps implies that some users use pandemic hashtags as a stepping stone to gain engagement for their posts.

Finally, House Selection games were found under #quarantinehouse. The posts are usually in the form of multi-choice games in which users are asked to choose one type of house to live in (mostly during quarantine times). Some of the games also involve other variations, such as choosing which celebrity to live with. Most of the content was posted by institutional accounts, such as television programme accounts or magazine accounts. Therefore, these posts may have a strong marketing purpose.

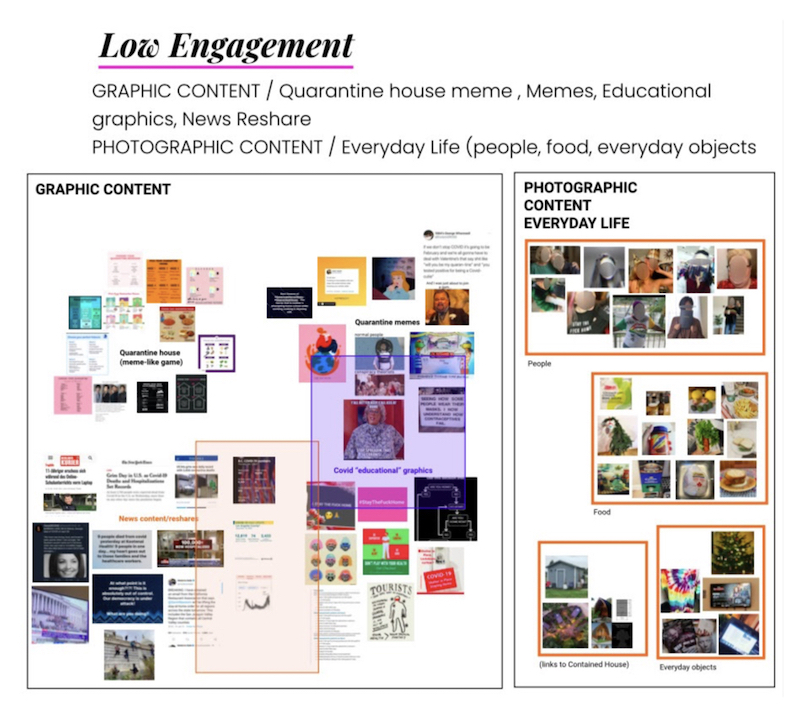

Low engagement posts

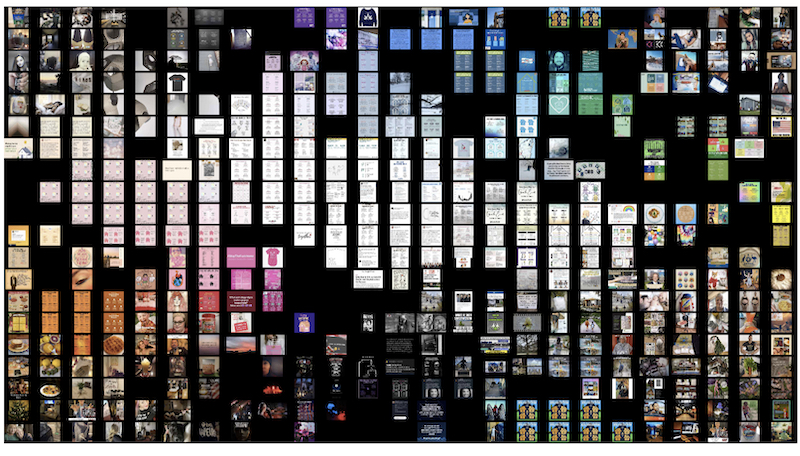

FIGURE 5. ImageSorter, Plot by Colour

FIGURE 5.1 and 5.2. ImageSorter, Plot by Colour

FIGURE 6. Figma, Manual Thematic Coding

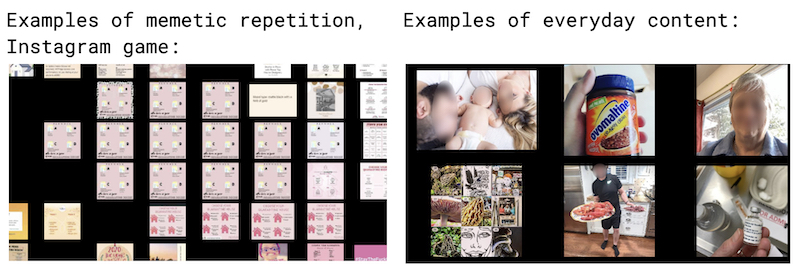

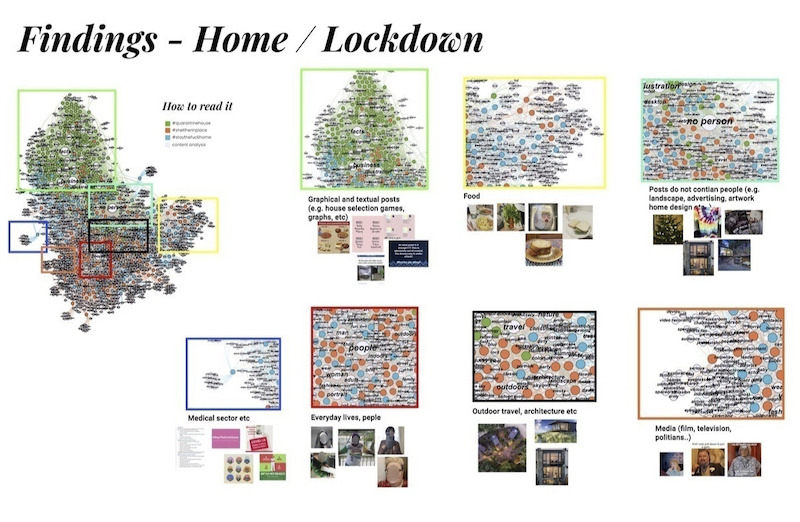

Among the low engagement posts (406 images) two major clusters have been identified: graphic content and photographic content.

Compared with the graphic content among high engagement posts, low-engagement graphic content content seems less commercially-driven. Within the graphic cluster, four categories were identified: House Selection Game, Quarantine/lockdown Memes, Covid Educational Graphics and News/Tweets Reshares.

The House Selection Game posts are in the same format as the ones in high engagement posts. They are very visually consistent and created a sense of visual repetition.

The Quarantine/lockdown Memes are mostly re-sharings of humorous content that reflects on and satirise the experience of living through a pandemic. These posts also include content from other platforms such as Twitter, Tumblr.

The Covid Educational Posts are graphics or illustrations that offer information about the pandemic. These include calls of responsible behaviours, such as wearing a mask and staying at home. There were also some overlaps with the meme category above, as some posts provide pandemic instructions in a humorous way.

The News/Tweets Reshares comprises mostly of screenshots from digital news outlets, which share current events or Covid-related news. When it comes to photographic content, we found three categories: People, Food and Everyday Object.

People post mainly include selfies or photos of other people engaged in everyday activities (e.g. working, showing off food). These were mostly taken in indoor settings, isolated, and as such do not include people wearing masks. Only one person took a selfie wearing both a mask and a face shield.

The Food posts include everyday-looking food images that are not overly aestheticised. Finally, Everyday Objects comprise a minority of posts. Again, they seem less aestheticized and more everyday-looking.

Overall, in the Specific Home-Lockdown hashtags (besides some exclusive posts such as container house design in the high engagement posts and news sharing in the low engagement posts) we could observe a large amount of graphic content in both high and low engagement posts. The memefied game where you should choose your ideal house to live through the pandemic was the predominant type of post in this cluster, highly popular in both the most engaged and the least engaged posts.

This predominance of this type of memefied game posts is also highly visible in our image-label network (Figure 7), where the large green cluster shows very closely related graphic and textual posts, all used by the #quarantinehouse.

It is also worth noting that some users may use the pandemic hashtags as an opportunity to increase the visibility of their posts even though they are not Covid-related, such as the case of the observed celebrity fan account.

FIGURE 7. Gephi, Image Label Network. Using Clarifai to automatically generate labels.

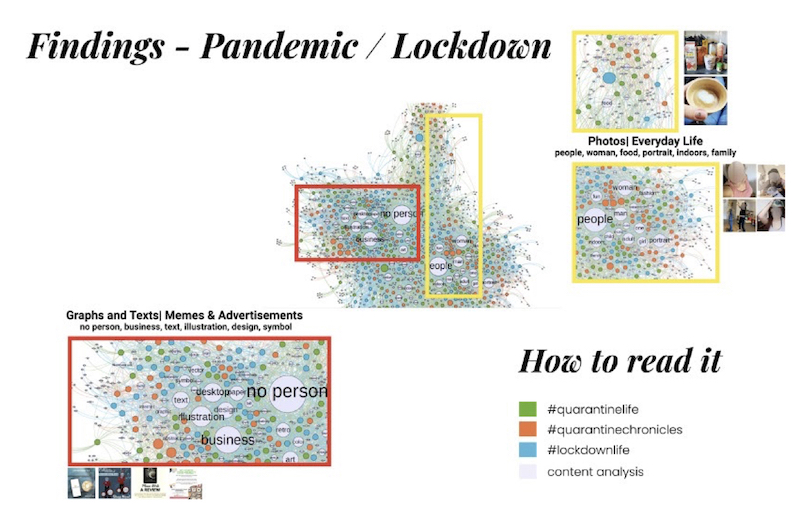

3) Pandemic/Lockdown related hashtags | Merged #3

The Pandemic/Lockdown hashtag include three hashtags, #quarantinelife, #lockdownlife, and #quarantinechronicles

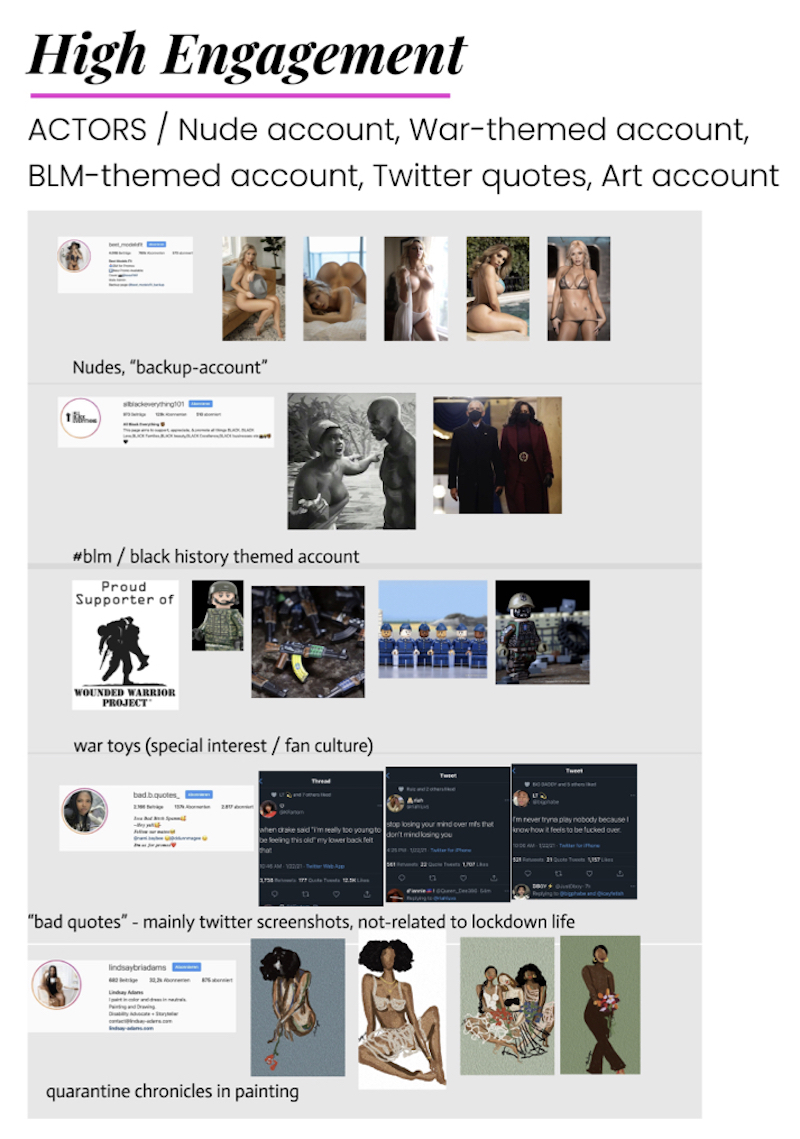

High Engagement

FIGURE 8. Figma, Manual Thematic Coding

When it comes to high engagement posts, 5 categories have been found: Nude account, war-themed account, BLM-themed account, Twitter quotes and Art account.

The most engaged users were almost all unrelated to the topic of the pandemic and its lockdown, maybe signaling a hijacking of these popular hashtags.

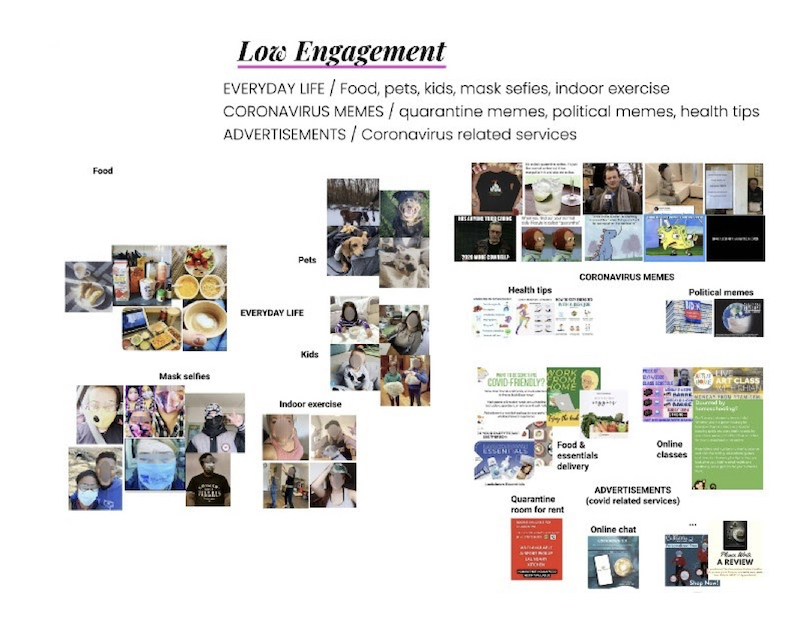

Low Engagement

FIGURE 9. Figma, Manual Thematic Coding

The results showed three main categories among the low-engagement posts (364 images): Everyday life, Coronavirus memes and Advertisements.

Hashtags were used to share a lot of everyday life content, rather than overly aestheticised content. These photographs were mostly taken in indoor settings, yet they featured a heavy presence of mask selfies.

In addition, nearly half of the images were text and graphical content, in particular, humorous memes dealing with the reality of the pandemic. Even commercial content was very closely related to coronavirus services.

Overall, low-engagement posts within this cluster were highly related to the pandemic, suggesting a strong correlation between this group of users’ postings and their choice of hashtags.

FIGURE 10. Gephi, Image Label Network. Using Clarifai to automatically generate labels.

The computer vision identified similar clusters to our categorisations:

4) Work-from-Home hashtags | Merged #4

The Work-from-Home hashtag include three hashtags, #homeoffice, #telework, and #workingfromhomelife

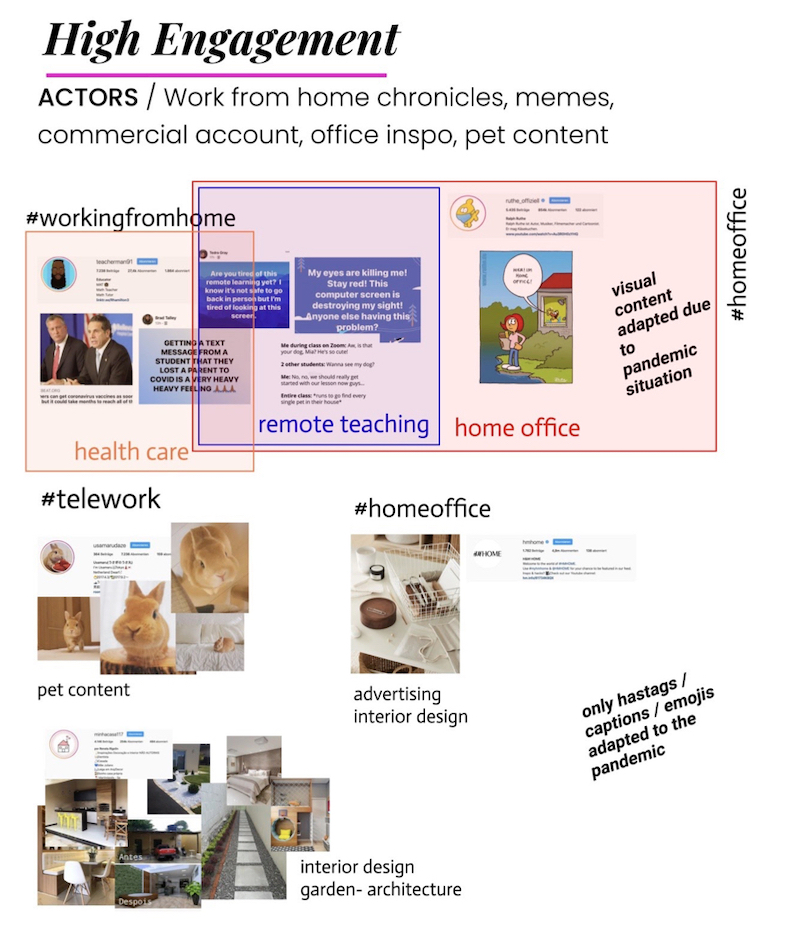

High Engagement

FIGURE 11. Figma, Manual Thematic Coding

Amongst high engagement posts, we identified 4 main categories: Commercial interior design, Inspirational interior and architecture design, Pandemic-related graphic content, and Pet content.

All pet content comes from a single account, that shares photos of a bunny under the hashtag #telework.

The general interior and architecture posts echo the inspirational strategies of the General Home Life / Aesthetics hashtag cluster, including also before and after shots of remodelations.

More directly related to the idea of telework, we also found a post with an inspirational #homeoffice setting, advertising the sale of stylish office supplies.

Finally, two of the high engagement accounts shared graphic content and news screenshots directly related to the pandemic, such as content about health care, remote teaching, and memes about working from home.

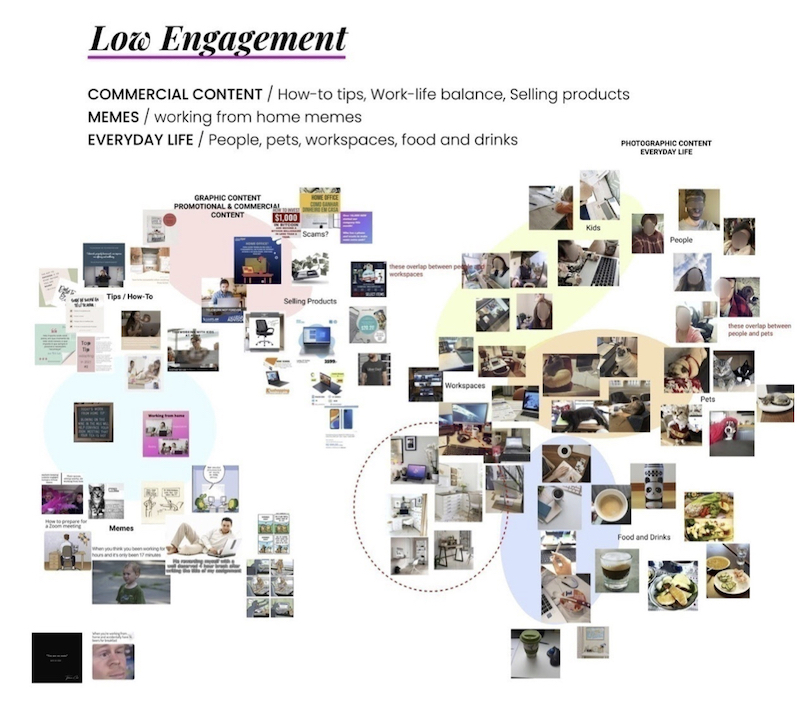

Low Engagement

FIGURE 12. ImageSorter, Plot by Colour

FIGURE 13. Figma, Manual Thematic Coding

The results showed three main categories among the low-engagement posts (405 images): Commercial Content, Memes, and Everyday Life.

Amongst the commercial content we could find a mix of graphic compositions and photographic content.

This category included How-To Work from Home posts and Tips for telework. These posts could be commercial in nature, promoting courses, tutorials, blog posts or books on how to manage telework (e.g. improve efficacy, wellbeing, avoid pain, pros and cons, how to prepare a zoom meeting). Within this category we could see a gendered aspect, with all posts focusing on work-life balance focusing on women, particularly women with children. According to our data set the combination of home-office and home schooling seemed to be a purely female challenge.

Some posts also directly attempted to sell office-related products (e.g. office chairs, laptops, phones and phone accessories) or services (e.g. legal advice about telework). We could also find promotional posts that verged on the side of scams, with promises to make money at home quick.

Some of these “tips” could have a humorous tone, thus overlapping with the meme category.

The Memes category included posts re-sharing humorous content that reflect on and satirise the experience of living through a pandemic. These were mostly cartoons and meme-generator content. These memes were often specifically related to the hashtags topics of working from home, relating to a sense of lack of productivity or issues with zoom communication.

Finally the Everyday Life category was mostly photographic content.

Overall, this content was not overly curated, idealised or aestheticised. Rather it had a diaristic feel.

Following closely the themes of the hashtags, photos of work spaces were common in this category. Although most photos felt organic, we could still observe a small cluster of highly-aestheticised photos of workplaces amongst these low engagement posts, reminiscent of homeinspo content.

This category of vernacular photography also included selfies, photographs of people in their workspace, and photos of kids working at home. Pets were also a common presence in this category, often overlapping with the idea of working from home, as these pets take over the workspace.

There were also several posts of food and drinks, most not in overly-aestheticised Instagrammable style but rather in a more spontaneous-looking styling. These images of food also frequently overlapped with a workplace setting, reflecting perhaps a collapse between work and break moments in context of the lockdown.

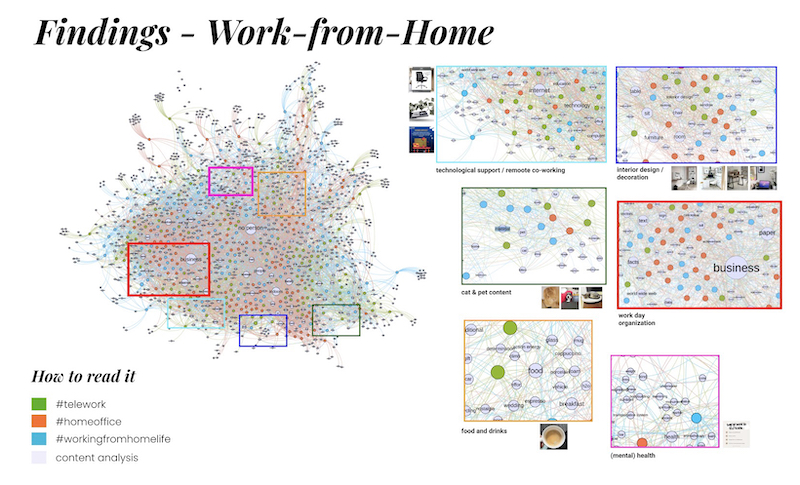

FIGURE 14. Gephi, Image Label Network. Using Clarifai to automatically generate labels.

Like with previous hashtag clusters, we can also observe similar groupings in the image-label network.

5) Emojis

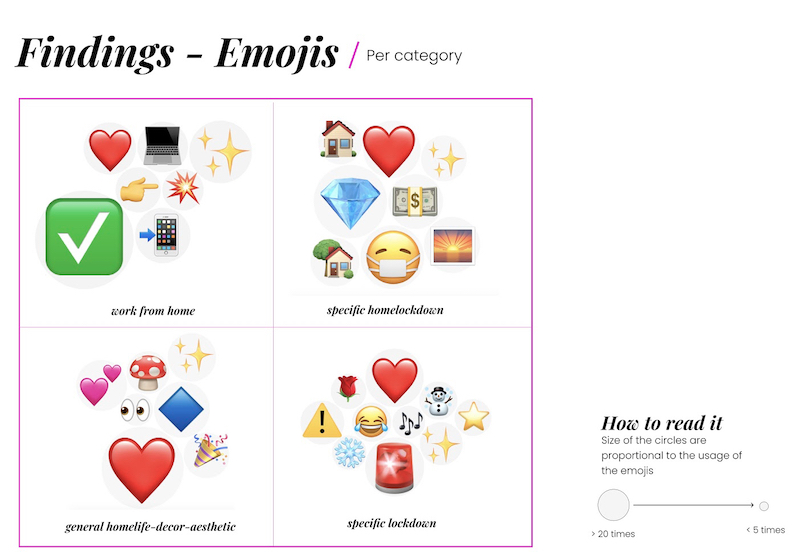

FIGURE 16. Figma, Emoji analysis. Used RAWGraphs to sort emojis by usage.

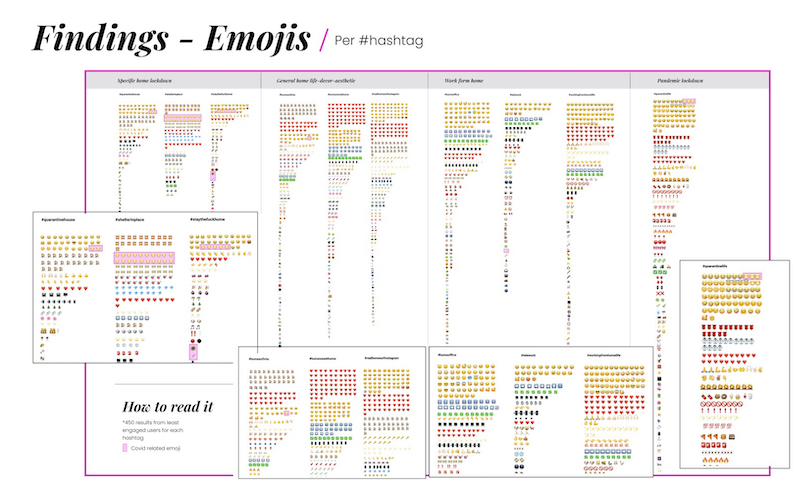

FIGURE 17. Figma, Emoji analysis. Used an online Textanalysis tool to extract emoticons from posts content and manually sorted them into columns.

Finally, we also did an emoji analysis of the captions per the whole category and per a single hashtag. For the whole category, we limited to 450 results from the most engaged users. On the other hand, for a single hashtag analysis, we took 450 results from the least engaged users for each hashtag.

To represent the dominant emojis, in the category visualization, we used the size of the emoticon. From this representation, we could find some relationships between the visual context and the emoji usage, such as the presence of tech emojis in the Work from home cluster, the mask emoji in the Home lockdown, and the overwhelmingly cute and positive emojis that reflect the idealized content of the Decor and aesthetic cluster.

On the other hand, for the single hashtag, we used quantitative visualization of used emojis and sorted them in vertical bars accordingly. From this approach, we could easily read the overall tone of the hashtag. For example, the ones that were predominantly including commercial and marketing posts, especially the house selling and buying advertising, such as #realhomesofinstagram, #quarantinehouse, and #homesweethome, included a large number of technical, repeated emojis. On the contrary, hashtags containing more personal posts, such as #staythefuckhome, #quarantinelife, and #quarantinechronicles contained more repeating warm emojis such as hearts, flowers, as well as a larger number of unique emoji usage.

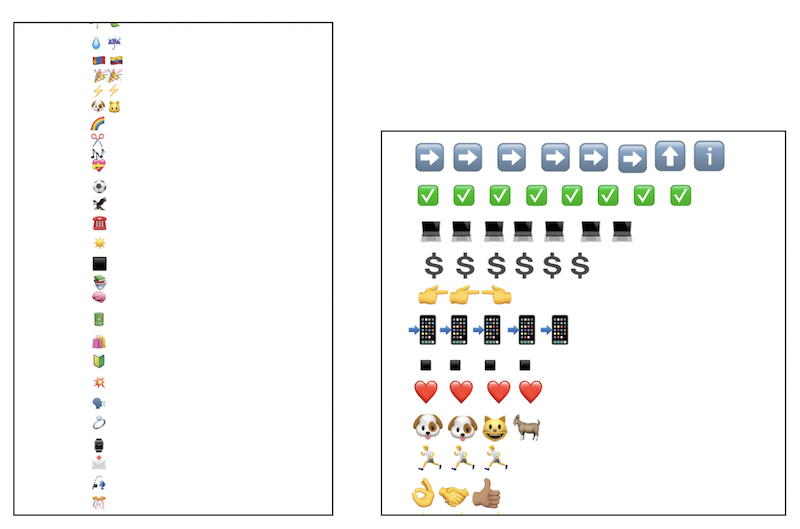

FIGURE 17.1 and 17.2. Figma, Emoji analysis. Used an online Textanalysis tool to extract emoticons from posts content and manually sorted them into columns.

Emoji analysis – #quarantinelife hashtag Emoji analysis – #workingfromhomelife hashtag

Another interesting insight is the very small presence of the COVID-19 related emojis. These appear only in non-commercial hashtags. In the least engaged posts analysis, they appear only 31 times. However, for the most engaged posts analysis, a smiley face wearing a mask is the most used emoticon for the Specific home lockdown category.

FIGURE 17.3. Figma, Emoji analysis. Used an online Textanalysis tool to extract emoticons from posts content and manually sorted them into columns.

Emoji analysis – #quarantinehouse hashtag

Finally, comparing these two analyses in general, there are not many differences in the tone of the hashtag. The only category that is slightly different is General home life-decor-aesthetic. In the most engaged posts analysis, the category is predominantly emotional, while in the least engaged posts this category tone looks highly commercial.

This project has focused on the visualities and aesthetics of domesticity on Instagram, in the context of the on-going pandemic. This research highlights the importance of studying a topic through multiple lenses and looking at distinct hashtag publics within it. As the findings above illustrate, the notion of the home can become multifaceted, as each of the hashtag clusters analysed showcased different facets of the same phenomena. Our thematic analysis and image-label network analysis allowed us to identify different representations of domesticity, ranging from diaristic and mundane photographs of everyday life (predominant amongst ordinary users and low-engagement posts), highly curated and aestheticised conceptions of the home (noticeable in the home decor hashtag cluster), or even imagined or hypothetical versions of domesticity (such as the ideal quarantine house memefied game that dominated the #quarantinehouse hashtag).

Exploring these distinct hashtag cultures demands an attentive consideration of the contextual information surrounding hashtag practices. For example, understanding the longevity, re-share practices, and shared conventions of hashtags such as #homesofinsta, #realhomesofinstagram, or #homesweethome helped to understand their remarkable visual consistency, amongst both popular accounts and low-engagement posts. This hashtag cluster emphasises the idea of the home as a physical dwelling – an architectural space, a space centred on decor. This can reveal links to consumer culture, as real estate agencies, architects, designers, home good brands engage with these hashtags. Consumption thus becomes linked to the construction of the notion of the home, and the home becomes a site for the expression of both individual tastes and socio-cultural distinctions (Bourdieu, 1996). This hashtag cluster also reveals an affective and experiential side of the home, through representations that emphasise a sense of cosiness.

The dominant cultural scripts of Instagram (Abidin, 2016) can seep into everyday representational practices within the platform, with ordinary users emulating the idealised and aestheticised conventions of popular users. Yet, our analysis illustrates how everyday uses of Instagram open a space for less curated, more diaristic representations. In all hashtags clusters, except for the home decor discussed above, there was a strong visual prevalence of posts showcasing everyday life and mundane experiences, in images that were not necessarily highly aesthetically curated or overly focused on high-production values. We identified various themes within this category – including people, masked selfies (showcasing examples of sociality and enjoyment of the outside world in the midst of a pandemic), pets, food and drinks, everyday objects, workspaces, etc. These often reflected varied domestic activities – such as cooking, baking, or working from home – or their by-products, offering a limited yet almost diaristic representation of everyday experiences in times of pandemic. Many of these images, with their seemingly more spontaneous framing, were reminiscent of the imagery of the early Instagram days, when the dominant onus of the platform was the instant sharing of everyday life. However, even though these images did not adhere to the highly idealised dominant conventions of contemporary Instagrammable aesthetics, they nonetheless visually represented mostly positive (or at least not overtly negative) aspects of everyday experience. The harsher realities of life under lockdown – experiences of loneliness, of living in unsafe home situations, of experiencing job precariousness or unemployment – were not immediately reflected in the visualities of our studied sample. It must be noted that reflections on these issues might have been relegated to the captions of the posts, as such a further analysis of the textual context is necessary. Our analysis seems to indicate that the predominant visualities within these hashtag publics relies on the dominant culture of positivity of Instagram, rather than offering a visual diary of the anxieties brought by the Covid crisis (Prins, 2020).

In addition to photographic user-generated content, there was also a large amount of graphic content in the studied sample, including memes. These memes, re-shared between accounts and across different platforms, opened space for more overt yet humoristic expressions of the frustrations of living through a pandemic and lockdown. News and other Covid-related informational content were also frequently re-shared. These practices of circulation of graphic content are not stereotypically associated with the dominant vernacular practices of Instagram, which are more commonly associated with user-generated photography (Gibbs et al., 2015). Instead, these practices reveal how visualities circulate cross-platforms, circumventing the expected uses of Instagram, and going beyond its technological affordances (for example by finding alternatives for re-sharing content, despite Instagram lacking a tool for that). This highlights the need for further visual cross-platform analysis (Pearce et al., 2020).

The sharing of graphic content was also frequently associated with commercial (albeit not necessarily popular) accounts. This points to a commercial appropriation of these hashtag publics and of the lockdown experience – with telework how-to tips, guides for a better work-life balance (not surprisingly all directed at women), and the overt selling of products and services closely related to the Covid-experience (such as food delivery, online chat services, or home office materials). These practices of hashtag co-option were even noticeable within posts and accounts that were only tangentially related or totally unrelated to the topic of hashtag, thus appropriating highly used hashtags to garner more engagement, in a clear strategization of social media’s logic of popularity (van Dijck & Poell, 2013). In one of the studied popular accounts, this hashtag co-option was acknowledged, as the posts were accompanied by disclaimers to “ignore the hashtags,” thus recognising that the hashtags bear no connection to the posts’ content.

Although not the core of our analysis, a preliminary comparative analysis between high and low engagement users reveals the potential to bring forward interesting correlations but also significant differences. For example, we could observe that some successful high-engagement accounts continue to operate with almost unchanged visual content, but adapt to new popular hashtag trends in the context of pandemic and home office.

The extent of the digital methods we were able to explore at this SMART Data Sprint was limited in their scope, and we acknowledge that these phenomena are no-doubt deserving of further scholarly attention and experimentation. Yet, these insights hopefully illustrate the richness of using an exploratory digital methods approach as an entry point to further qualitative research of social media visualities.

Abidin, C. (2016). “Visibility labour: Engaging with Influencers’ fashion brands and #OOTD advertorial campaigns on Instagram.” Media International Australia, 161 (1), 86–100.

Banet-Weiser, S. (2012). Authentic TM: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture. New York: New York University Press.

Barbour, K. & Heise, L. (2019). “Sharing #home on Instagram.” Information, Communication & Society, 172 (1), 35–47.

Caldeira, S. P., De Ridder, S. & Van Bauwel, S. (2020). “Between the Mundane and the Political: Women’s Self-Representations on Instagram.” Social Media + Society, 6 (2), 1–14.

Gibbs, M. et al. (2015) “#Funeral and Instagram: death, social media, and platform vernacular.” Information, Communication & Society, 18 (3), 255–268.

Hermes, J. & Hill, A. (2020). “Television’s undoing of social distancing.” European Journal of Cultural Studies, 23 (4) 655–661.

Kay, J. B. (2020). “Stay the fuck at home!”: feminism, family and the private home in a time of coronavirus.” Feminist Media Studies, 20 (6), 883—888.

Leaver, T., Highfield, T. & Abidin, C. (2020). Instagram: Visual Social Media Cultures. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Manovich, L. (2017). Instagram and Contemporary Image. Retrieved from http://manovich.net/index.php/projects/ instagram-and-contemporary-image

Marwick, A. (2013). Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, & Branding in the Social Media Age. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Omena, J.J.; Rabello, E & Mintz, A. (2020). “Digital Methods for Hashtag Engagement Research”. Social Media + Society, Special Issue: Studying Instagram Beyond Selfies, edited by Alessandro Caliandro and James Graham. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120940697

Pearce, W. et al. (2020). “Visual cross-platform analysis: digital methods to research social media images.” Information, Communication & Society, 23 (2), 161–180.

Prins, A. (2020). “Live-archiving the crisis: Instagram, cultural studies and times of collapse.” European Journal of Cultural Studies, 23 (6), 1046–1053.

Software References

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009). Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks. Third International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

Danowski, J. A. (2013). WORDij version 3.0: Semantic network analysis software. Chicago: University of Illinois at Chicago.

Davis, J. (n.d.). WordTree. Available at https://www.jasondavies.com/wordtree/

Figma.inc (n.d.) Figma. Available at https://www.figma.com/

Maier, N. (2019). DownThemAll (Version 4.1). Available at https://www.downthemall.org/

Mauri, M., Elli, T., Caviglia, G., Uboldi, G., & Azzi, M. (2017). RAWGraphs: A Visualisation Platform to Create Open Outputs. In Proceedings of the 12th Biannual Conference on Italian SIGCHI Chapter (p. 28:1–28:5). New York, NY, USA: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3125571.3125585. Available at https://rawgraphs.io/

PhantomBuster. (2021). Instagram Hashtag Collector. Available at https://phantombuster.com/automations/instagram/5391/instagram-hashtag-collector

Rieder, B. (2019). Textanalysis (Version 0.2). Available at http://labs.polsys.net/tools/textanalysis/

Steinbock, Daniel. Tagcrowd. Available at https://tagcrowd.com/

Visual Computing. (2018). ImageSorter. Visual Computing Group at the HTW Berlin. Retrieved from https://visual-computing.com/