Project title: Anti-Feminist and Anti-LGBT Discourse Networks in Brazil: qualifying social media engagement around the 2018 presidential election

Lead: Horacio Sívori; Elaine Rabello; Bruno Zilli

Team members: Alessia Mussio, Ana Pinto-Martinho, Elena Aversa, Fabio Gouveia, Ilo Aguiar, Johnnatan Messias, Katherina Grishaeva, Shenglan Qing, Simone Evangelista Cunha (see Appendix for team mini bios)

Key Findings

Introduction

Research Questions

Query Design & Visual Protocol

Methodology

Findings

Discussion

References

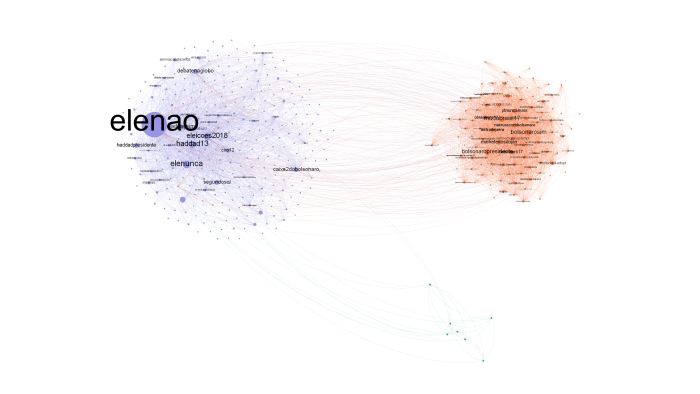

The behaviour of digital actors during the 2018 Brazilian general election period and arguably thereafter shows that feminist and sexual politics issues, rather than distinct, singled out causes, were addressed in an embedded manner, within broader, as a rule polarized, online political issue spaces. The traction that the hashtags #EleNão and #EleSim exercised among multiple publics illustrates this. While the former conflated feminism and the defense of democracy on one pole of presidential election issue spaces, its reverse appropriation, eventually condensed by the latter, conflated anti-feminism with everything else Bolsonaro represented to his supporters during the election and immediately thereafter.

This has grave theoretical and political consequences if Bolsonaro’s success indicates the rise of a fascist movement in Brazil (Cesarino, 2020), as observers—sometimes ultra-conservatives themselves—claim. As evident since our initial front-end collection of feminism and sexual politics pages on Facebook, and at every step and platform thereafter, we are not to see anti-rights grammars, discourse, narratives, and rethorics only (or at all) within exclusive anti-rights issue spaces. Their articulation is much more complex, and requires some sophistication in the analytical instruments we construct to address it. Perhaps the notion of intersectionality as the variable articulation of different markers of difference, some conspicuous, some tacit, but all always present, might help unpack what we so far clumsily refer to as embeddedness and conflation.

The 2018 Brazilian presidential election was testimony to the power of social media to amplify the reach and effectiveness of “fake news” and other disinformation tactics (Coding Rights, 2018). Social media platforms’ capacity to isolate audiences from other information sources intensified the classic power of moral panics to instill anger and fear against their scapegoats in specific publics (Irvine, 2006). In the context of an ongoing global backlash against women’s rights, LGBT rights, affirmative action, and the defence of human rights (Paternotte & Kuhar, 2018), social media have become an echo chamber for the unbridled propagation of what feminists have aptly called anti-rights activism (e.g., against gay marriage, against the right to abortion, etc.), and its means to engage and mobilize individuals and communities. In response to those attacks, feminists, LGBTs and their allies actively resist those ofenses, engaging them in different ways on social media as well, often using irony, e.g., in their frequent parody of homophobic and misogynistic discourse. However, while communications rights activists, digital researchers and, particularly, feminists within those fields have become increasingly sensitive to the logic of surveillance embodied in processes of datafication, as well as to their market-driven exploitative effects (Shephard, 2016), the productive role of social media and disinformation tactics in sexual politics is still open to inquiry. In that direction, the object of this research lies on the role of social media platforms in the production and dissemination of anti-rights discourse, as well as in the responses it generates.

We set out to address the shape that anti-feminist and anti-LGBT issue networks (Rogers, 2018) took on social media platforms in Brazil during the 2018 electoral period, and the sorts of networks and forms of engagement the platforms that host them facilitated. Our framework of analysis combined insights from current literature on “anti-gender” and “anti-sexual rights” mobilization on- and off-line, and our own exploratory ethnographic observations on what we have termed anti-feminist and anti-LGBT discourses on social media, and on feminist and LGBT resistance to those discourses online as well. According to the literature on the subject (see Almeida, 2019; and Leite, 2019) and in our observation, content shared in those specialized networks involving, for example, the deployment of homophobic and misogynistic hate speech, rely on moral panics to mobilize political support to ultra-conservative political actors.

Our main research questions, as laid out below, are about modes of engagement in anti- and pro-feminist and LGBT issue networks, and platform affordances favourable to their connectivity. The mapping of, and making hypotheses about, how engagement is generated within those issue spaces are empirical ways of inquiring about the purposes and the effects of their connections, beneath what is readily accessible to the lay user or observer. To those ends, we repurposed Richard Rogers’ “critical analytics” (2018:5-7), devised specifically for social—and admittedly political—issue networking, where what matters, instead of a supposedly universal, indistinct value of popularity, is the network’s power to engage in complex ways. Beyond visible content at the front end, and beyond actors’ popularity, digital methods should aid us to describe with precision the specific role and evolution of a variety of social media platform affordances in producing the political conditions to mobilize political support (see Cesarino, 2020, on the case of WhatsApp in the 2018 election).

On Facebook, Twitter and Youtube, we conceived an exploratory design to addresses two broad questions:

- What platform-specific objects (posts, shares, replies, etc.) and criteria (metrics, etc.) suggest an engagement with anti- and pro-rights discourse and the formation of anti- and pro-rights issue spaces in Brazil;

- How digital actors and contents characterized as pro- and anti-rights behave within and across platforms.

Query Design & Visual Protocol

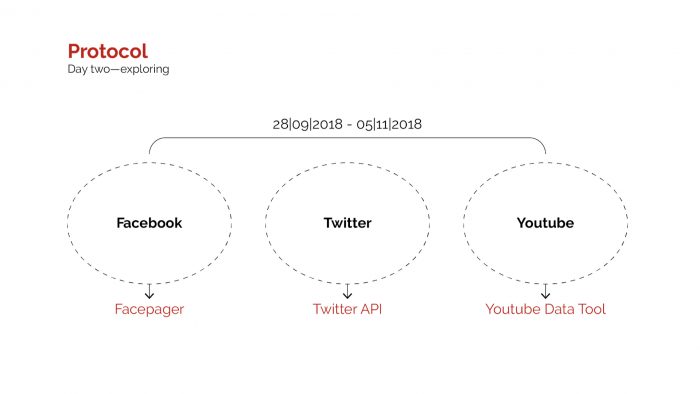

A preliminary decision was made to focus our analyses of all three platforms on the six-week time lapse around the 2018 general election. Although the databases we used were constructed using other criteria (see below), all digital objects contemplated in this exploratory exercise were date-marked between 29 September and 5 November, 2018—the time frame reference for this project.

Platforms and main extraction tools

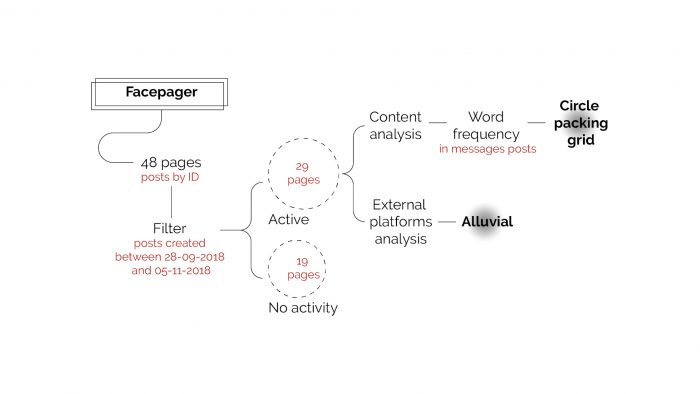

1) FACEBOOK

The original dataset was assembled in October and November, 2019. A research profile was created using the ‘research persona’ methodology (Dieter et al., 2019). From that profile, on a clean browser, we conducted queries on the platform’s own front-end search tool, using keywords that signalled the main controversies involving feminism, gender and sexuality during the election campaign: gênero, família, feminismo(s), feminista(s), feminino, cristão, evangélico(s), aborto, kit gay, PL 122 (Federal bill proposal designed to criminalise homophobia), mamadeira de piroca (literally “dick baby-feeding bottle,” a meme showing a penis-shaped feeding bottle nipple, also widely shared during Bolsonaro’s presidential campaign), heterofobia, heterofóbico, homofobia, macho/machismo/machista, esquerda (left). We selected search results that led us to Facebook Pages, and made a further qualitative selection of pages considering the contents of their Home, About, Events, Photos, Videos, Community, Groups fields at the time (October-November 2019), as well as their latest Timeline. Pages unrelated to either anti- or pro- rights discourse were discarded. 48 Pages were selected considering their diversity of scope, their amount of followers and likes, the variety of forms of engagement by owners, followers, and viewers. Those pages were subsequently classified as anti-rights (28 pages), pro-rights (17 pages) and neutral (3 pages), by their content. Additionally, all URLs listed at their Home, About, Events, Photos, Videos, Community, and Groups fields of those pages were extracted (85 URLS in total).

Facebook analysis protocol

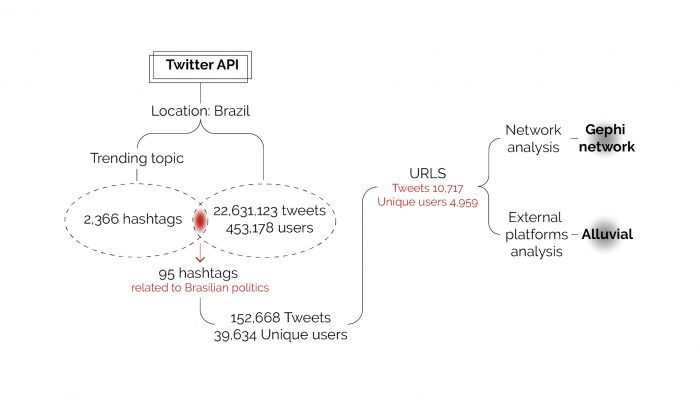

2) TWITTER

Our project had access to a database of 22,631,123 tweets and 453,178 users located in Brazil. To construct that database, a script was written to gather “data from the 1% random sample of all tweets, provided by the Twitter Stream API” (Messias et al, 2017:2). Since “geographic coordinates are available on Twitter only for a limited number of users (i.e. < 2%)” (idem), a filter based on user timezone was applied to infer geographical location. For an extensive period of time, the hashtags that made the top trending topics in Brazil were extracted every five minutes, using the Twitter API.

Besides selecting the digital objects within the protocol’s period of reference, we ranked the top ten hashtags (by number of users and number of tweets) on each date of that period. We generated a spreadsheet with the frequency of the most used hashtags, and a CSV file with 150,000 tweets and unique users of the hashtags in the sample, in order to select the ones related to national politics. To filter by relevance, we also eliminated those with less than 200 occurrences. Out of 2,366 hashtags, Brazilian members of the team manually selected 95 “political” hashtags, and classified them as pro-rights, anti-rights, and unrelated or ambiguously related to feminism and sexual politics.

Twitter analysis protocol

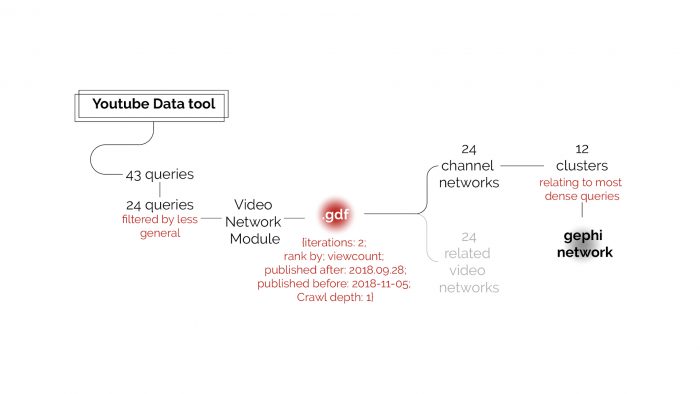

3) YOUTUBE

From an original list of 43 tested earlier at the front end and on YouTube Data Tools queries, we selected 24 terms to query on the Video Network Module: abortista, aborto, antifeminista, conservadorismo, feminismos, doutrinação (indoctrination), feminista, gayzista, gayzismo, gênero, heterofobia, heterofóbico, homofobia, homossexualidade, homossexualismo, ideologia de gênero, kit gay, kitgay, kit-gay, LGBT, machismo, machista, mamadeira de piroca, PL 122, pro vida, provida, pró-vida (pro-choice). We thus generated a list of top-ranked networked videos and their respective channels for the protocol’s reference period (29 September to 5 November 2018).

Youtube analysis protocol

1) FACEBOOK

|

Step |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

Source |

Posts from 48 feminism and sex politics Facebook pages – 28 anti-rights – 17 pro-rights – 3 neutral (40 scroll-downs per page) |

Text posts from 29 feminism and sex politics Facebook pages active at the time |

URLs posted in 29 feminism and sex politics Facebook pages active at the time |

|

Time Frame |

From time of page creation until 28 January 2020 |

29 September to 5 November 2018 (general election period) |

|

|

Tool |

Facepager (web page data retrieval tool) |

WordArt (online word cloud creator) |

Adobe Illustrator + Raw Graph |

|

Data Output |

– 48 spreadsheets (one per retrieved post) indexed by: – extraction time – post ID (URL) – timestamp – creator – type: status, text, link, image, video – status: shared, added, mobile status update, shared story (URL, external) – caption (if any) – textual content |

– 3 diagrams of top 50 words, one in the whole sample of Facebook pages, and one in each sub-sample: anti- and pro-rights |

– Distribution of web sources posted in Facebook pages in the sample, indexed as anti- and pro-rights |

|

Visual Output |

– Three circle packing grids of most used terms on feminism and sex politics Facebook pages: – general frequency (figure 1) – anti-rights pages (figure 2) – pro-rights pages (figure 3) |

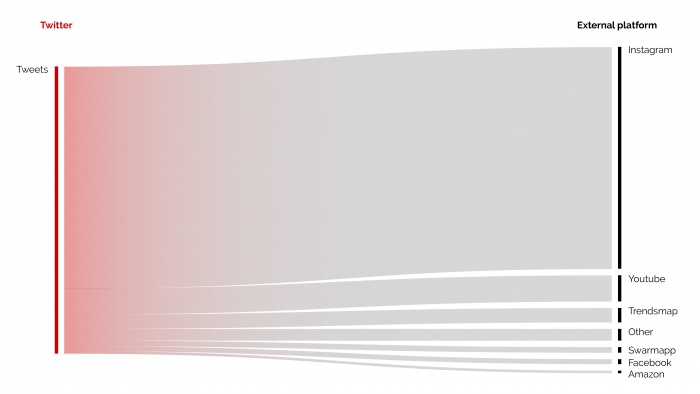

– One alluvial diagram of URLs posted in feminism and sex politics Facebook pages (indexed as anti- and pro-rights) and type of URL on the outside end (plaforms and other websites) |

|

2) TWITTER

Metrics were generated for the top words used in the Twittersphere during the protocol’s period of reference, showing the reason of tweets containing (1) “political” hashtags and of their users; (2) gender and sexual politics hashtags, and of their users; and (3) anti- and pro-rights hashtags, and of their users. RawGraph, WordArt and Gephi were produced to visualize those comparative metrics.

Additionally, in an attempt to explore cross-platform dynamics, we analysed the orientations of all URLs embedded in “political” tweets within the sample.

3) YOUTUBE

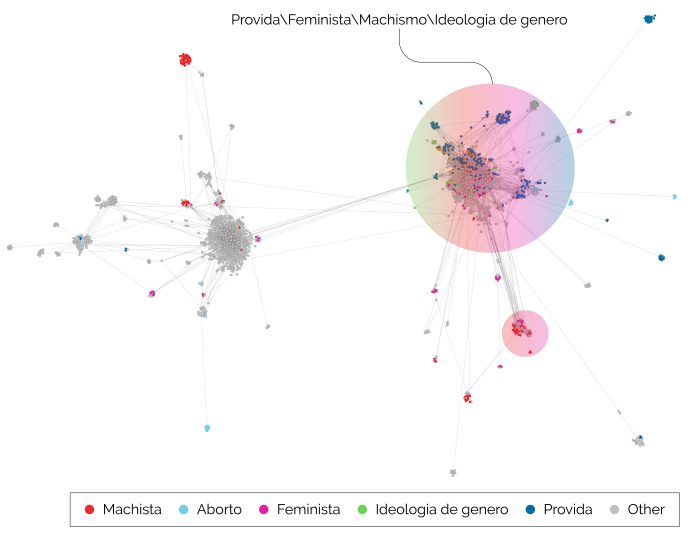

From an initial list of 24 channel networks, 12 clusters were selected, the ones resulting from the more successful queries, and a network graph was generated using Gephi, depicting how the top-ranked videos from the channels in the network are placed relative to each other when applying YouTube’s “related video” algorithm.

1) FACEBOOK

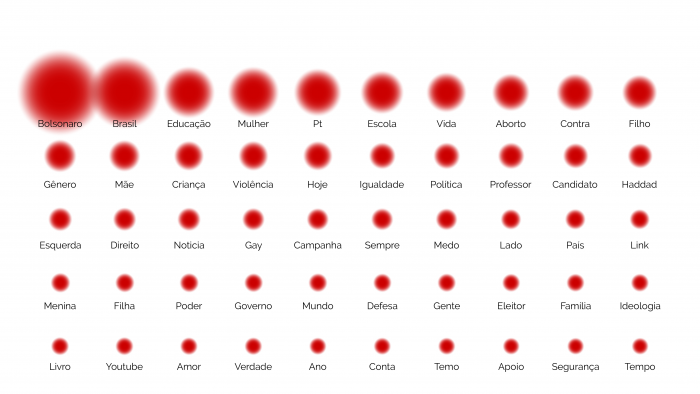

FIGURE 1. Top words in all verbal post content in all feminism and sexual politics-themed Facebook pages active during the 2018 Brazilian electoral period. N=29. Circle Packing Grid.

FIGURE 2. Top words in all verbal post content in anti-rights feminism and sexual politics-themed Facebook pages active during the 2018 Brazilian electoral period. N=15. Circle Packing Grid.

FIGURE 3. Top words in all verbal post content in pro-rights feminism and sexual politics-themed Facebook pages active during the 2018 Brazilian electoral period. N=11. Circle Packing Grid.

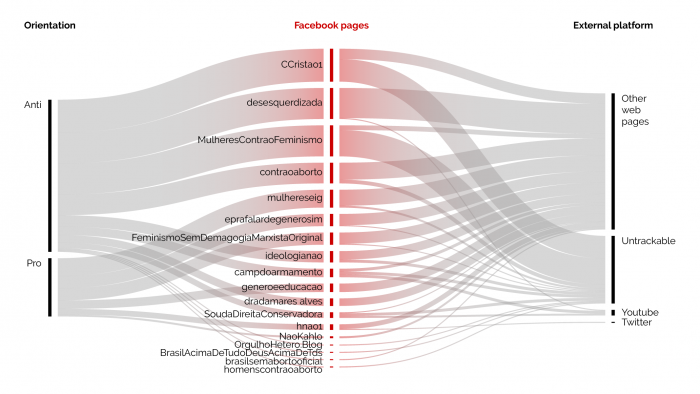

FIGURE 4. Distribution of links posted in feminism and sexual politics-themed Facebook pages active during the 2018 Brazilian electoral period, indexed as anti- and pro-rights. Type of URL on the outside end. Alluvial diagram. N=29.

2) TWITTER

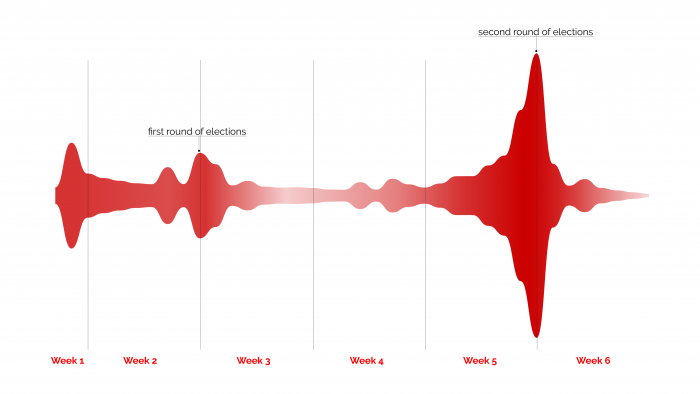

FIGURE 5. Twitter. Stream of political hashtags during the general election period.

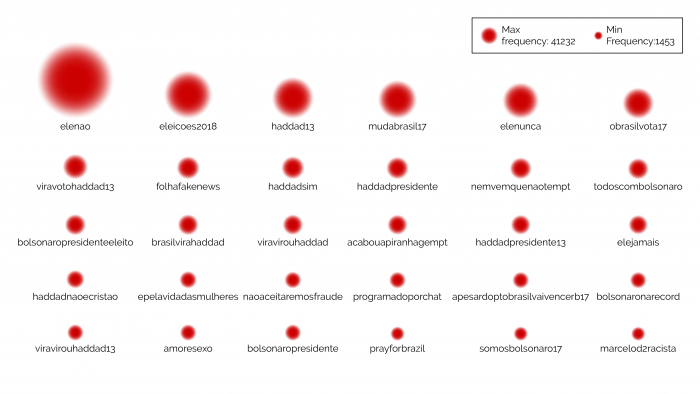

FIGURE 6. Twitter. Political trending Hashtags during the 2018 general election period.

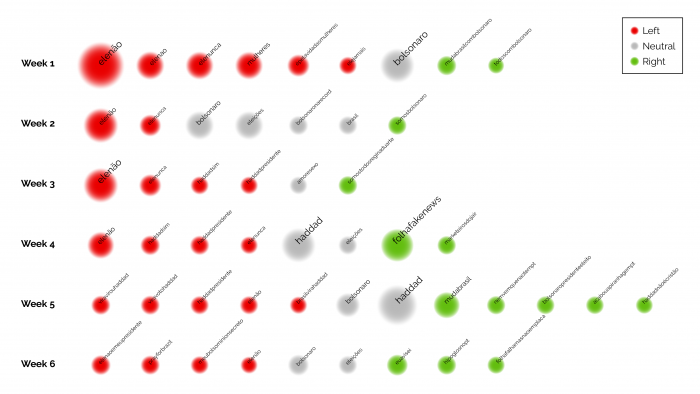

FIGURE 7. Twitter. Political hashtags by week, classified by issue positionality.

FIGURE 8. Twitter. Trending Hashtags during the 2018 general election period, by topic.

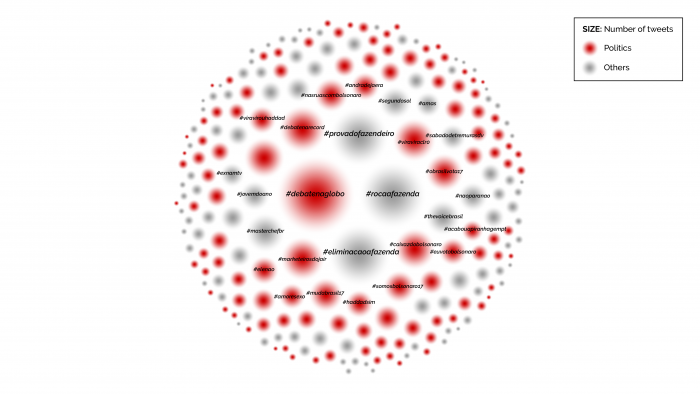

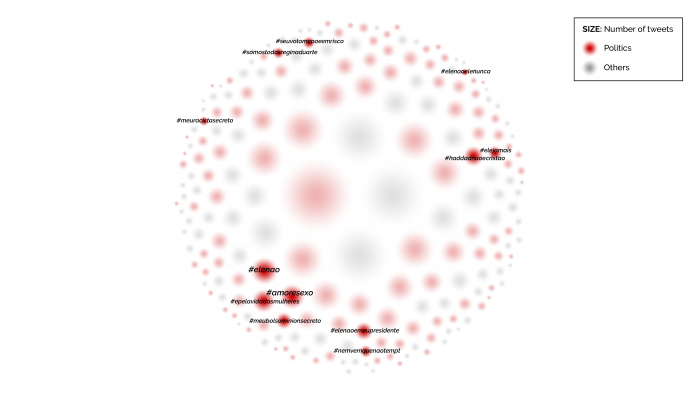

FIGURE 9. Twitter. Trending hashtags during the 2018 general election period, by topic, feminism and sexual politics highlighted.

FIGURE 10. Twitter. User-hashtag network. Nodes are hashtags and edges are users. Node size indicates hashtag frequency. Distance between nodes represents the density of hashtag content connection.

FIGURE 11. Twitter. URLs embedded in political hashtagged Tweets.

2) Youtube

FIGURE 12. Channel network hosting the top-ranked videos, by view-count. Each node is a channel. The edges and space between depicts the strength of their connection. Colors indicate a video’s main topic, according to YouTube’s own thematic classification. Background tinted circles round the larger channel clusters.

In the Gephi network graph shown in FIGURE 12, if a video from one channel points to a video of another channel, an edge is created. The more often that happens, the more weight the connection gets. That gives us an idea of the relative weight of viewers’ engagement with different issues (as predicted or influenced by YouTube’s algorithm), as well as the proximity or separation between digital actors (or, rather, the degree of their traction), in this case videos and channels. Additionally, some clusters were coloured applying relevant terms from YouTube’s own thematic classification of the videos. Note that YouTube does not share the criteria for that classification.

1) FACEBOOK

In general, most posts were generated by the page runners themselves, and many external URLs are YouTube or Twitter links. Bolsonaro’s candidacy was successful at monopolizing public attention, particularly on anti-rights pages. Anti-rights attention tended to concentrate more in a restricted number of terms, mostly election-related, while pro-rights terms seem more evenly distributed and varied in scope. Many terms are common to both segments, although in our qualitative assessment we observed that they are used with different, often contrary meaning and intention.

2) TWITTER

Note the prevalence of the feminist #EleNão slogan, soon embraced as a voice of resistance across the left-wing spectrum, over the first few weeks of the timeframe, with its peak on 29 September, when street demonstrations under that slogan took place across the country. #EleNão is emblematic of the extended presence of pro-rights discourse not only in feminist, LGBT or otherwise pro-rights issue spaces per se, but mainly, as Twitter metrics show, embedded in multi-issue spaces of resistance against Bolsonaro, and fascism.

3) YOUTUBE

The pattern of distribution of top-ranked videos and their hosting channels is typical of a polarized issue space. The tagged categories associated with issues that framed the dataset are unequivocally concentrated in different clusters, either next to, or visibly distant from each other. At times they appear mainly in one cluster, like Provida (blue dots) and Ideologia de Gênero (green dots) densely connected to each other within the larger cluster of channels. At times they are spread in various clusters, like Machista, sometimes densely connected, but also distant from the main issue spaces. The presence of the same label clustered within different poles may indicate the presence of some terms, albeit with probably opposite meanings and uses in both pro- and anti-rights videos. The high prevalence of grey dots at the center of the larger “poles” also show how embedded feminism and sexual politics issues are in “other” issue spaces in the YouTube videosphere, in this sample probably, from the evidence of other platforms, around the presidential candidates and other electoral politics themes.

FINAL REMARK

Rather than substantive or innovative, we deem the modest results shown in this report useful at assessing the value of the type of digital methods that, with our limited skills and capacities, we were able to explore at this SMART Data Sprint, vis-a-vis the essentially qualitative purposes of our research. In that vein, our first remark is about the partial, exploratory nature of the analytic processes we described. As noted along the report, particularly with regard to connections across platforms, some combined-methods empirical explorations are pending—mostly emergent from insights provided by this first exercise, but to a certain degree anticipated by the literature and our own observations.

Almeida, Ronaldo de. Bolsonaro Presidente: Conservadorismo, evangelismo e a crise brasileira. Novos estudos CEBRAP, 38(1), 185-213. Epub May 06, 2019 Available at: <https://dx.doi.org/10.25091/s01013300201900010010>.

Association for Progressive Communications. Feminist internet ethical research practices. 2019. Available at: <https://www.apc.org/en/pubs/feminist-internet-ethical-research-practices>.

Cesarino, Letícia. Como vencer uma eleição sem sair de casa: a ascensão do populismo digital no Brasil. Internet e Sociedade 1(1): 91-120, 2020. Available at: <https://revista.internetlab.org.br/serifcomo-vencer-uma-eleicao-sem-sair-de-casa-serif-a-ascensao-do-populismo-digital-no-brasil/>

Coding Rights. Data and Elections in Brazil 2018. Coding Rights. 2018. Available at: <https://www.codingrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Report_DataElections_PT_EN.pdf>.

Dieter M, Gerlitz C, Helmond A, Tkacz N, van der Vlist FN and Weltevrede E. Multi-situated app studies: Methods and propositions. Social Media + Society, 5(2), 1–15, 2019, June 7. Available at: <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2056305119846486>.

Feminist Principles of the Internet. N/D. Available at: <https://feministinternet.net/en>.

GenderIT. “We cannot be what we cannot see”: Mapping gaps in internet and information society. 2017. Available at: <https://www.genderit.org/node/5003/>.

Irvine, J.M. Emotional scripts of sex panics. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2006, 3, 82. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/srsp.2006.3.3.82.

Leite, V. “Em defesa das crianças e da família”: Refletindo sobre discursos acionados por atores religiosos “conservadores” em controvérsias públicas envolvendo gênero e sexualidade. Sex., Salud Soc. (Rio J.) [online]. 2019, n.32 [cited 2020-01-12], pp.119-142. Available at: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1984-64872019000200119&lng=en&nrm=iso>. Epub Sep 09, 2019. ISSN 1984-6487.

Melo et al. WhatsApp Monitor: A Fact-Checking System for WhatsApp. Proceedings of the Int’l AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (ICWSM’19). 2019. Munich, Germany. June, 2019. Available at: <https://homepages.dcc.ufmg.br/~fabricio/download/icwsm2019-whatsapp.pdf>.

Messias, Johnnatan; Vikatos, Pantelis; Benevenuto, Fabrício. White, Man, and Highly Followed: Gender and Race Inequalities in Twitter. In Proceedings of the IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence (WI’17). Leipzig, Germany. August 2017. Available at: <https://people.mpi-sws.org/~johnme/pdf/messias_wi17_inequality.pdf>

Paternotte, D & Kuhar, R. Disentangling and Locating the “Global Right”: Anti-Gender Campaigns in Europe. Politics and Governance. 2018, Volume 6, Issue 3, pp.6–19. Available at: <https://www.cogitatiopress.com/politicsandgovernance/article/view/1557/1557>. ISSN: 2183–2463. http://dx.doi.org/10.17645/pag.v6i3.1557.

Resende et al. A System for Monitoring Public Political Groups in WhatsApp. In Proceedings of the Brazilian Symposium on Multimedia and Web (WebMedia 2018). Salvador, Brazil. October, 2018.

Available at: https://www.eleicoessemfake.dcc.ufmg.br/assets/articles/webmedia2018.pdf

Rezende et al. Analyzing Textual (Mis)Information Shared in WhatsApp Groups. Proceedings of the Int’l Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Web Science (WebSci’19). Boston, USA June, 2019. 2019 Association for Computing Machinery.

Available at: <https://www.eleicoessemfake.dcc.ufmg.br/assets/articles/webmedia2018.pdf>. ACM ISBN 978-1-4503-6202-3/19/06>. https://doi.org/10.1145/3292522.3326029.

Rogers, R. Otherwise Engaged: Social Media from Vanity Metrics to Critical Analytics. International Journal of Communication. 2018. IJoC, 12, pp.450-472. Available at: <https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/22792936/Rogers_IJOC_6407_30088_3_PB.pdf>.

Shephard, N. Big Data and Sexual Surveillance. APC, 2016. Available at: <https://www.apc.org/sites/default/files/BigDataSexualSurveillance_0.pdf>.

Team Members

Johnnatan Messias. Data scientist, second-year PhD student at the Max Planck Institute for Software Systems (MPI-SWS), Germany.

Fábio Gouveia, PhD. Public Health Technologist at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Brazil. Leader of the Science, Data, Networks and Metrics Research Group (Scimetrics). He does Information Science research on Metrics (Scientometrics, Webometrics, Altmetrics, Science and Technology Indicators and Innovation), Digital Methods, STS, Data Science and Blockchain Technology, and Science and Health Communication, with emphasis on Internet and social media.

Elena Aversa, MA. Communication and information designer based in Italy. Her MA thesis looked at disinformation on Facebook in Italy. She collaborates with Density Design, Accurat, Pagella Politica SRLS and Water Grabbing Observatory.

Ana Pinto Martinho. Online publisher and researcher at the Science and Communication Laboratory of ISCTE-IUL, Portugal. She produces and collaborates for a number of online news media outlets. She teaches data journalism data and visual journalism and is currently working on her PhD at ISCTE – Communication, Culture and Information Technologies.

Ilo Aguiar, PhD. Researcher at iNOVA Media Lab, Portugal. His main research is on audience interaction and data visualizations in news media.

Shenglan Qing. PhD candidate in Audiovisual Communication and Advertising at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Catalunya. Her dissertation research focuses on reality television programs on Twitter in Spain and Weibo in China.

Simone Evangelista Cunha, PhD. Researcher and journalist, currently a postdoctoral researcher in the Communications Department at Fluminense Federal University, Brasil, working on cultural and affective practices on digital platforms in contemporary Brazil. Her interests include labour reconfiguration and the popularization of anti-feminist and anti-scientific discourses on YouTube.

Ekaterina Grishaeva, PhD. Assistant Professor at the Department of Philosophy at the Ural Federal University (Yekaterinburg, Russia). She also leads a research project on social media and the Russian Orthodox Church. Her current research interests include the theory of mediatization, the impact of digital technologies on the transformation of post-Soviet societies, and Internet politics.

Acknowledgements

APC – Association for Progressive Communications

IDRC – International Development Research Center

FIRN – Feminist Internet Research Network

Project Digital networks, backlash and datafication in Brazil, by Horacio Sívori, Elaine Rabello and Bruno Zilli

FAPERJ – State of Rio de Janeiro Research Foundation

Project Social networks as a field for health knowledge circulation, by Elaine Texixeira Rabello

FAPERJ ARC E-26/010.000346/2017

CAPES – Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel, Brazil

Project Networked violence and the reproduction of inequality: online hate speech and anti-rights activism in different scales and contexts, by Horacio Sívori

CAPES-PRINT IMS/UERJ 88887 311765/2018-00